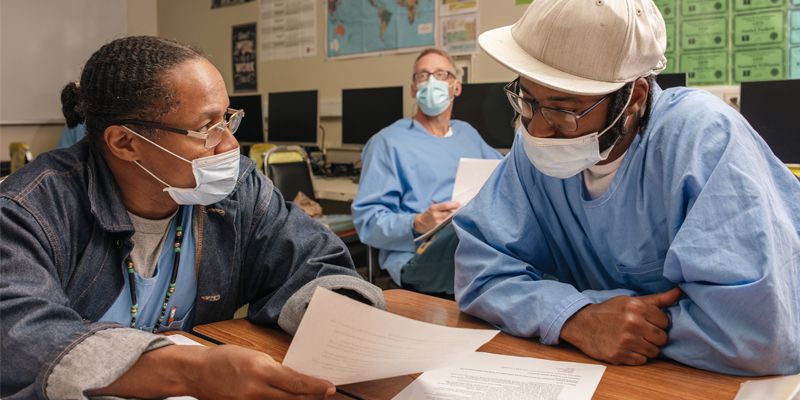

Students walk to and from classes with books in hand. Some stand around the yard, discussing philosophical concepts from their latest assigned readings. The scene looks similar to that found on any campus quad—except the students are gathered in a prison yard, and the college is located in San Quentin State Prison.

Mount Tamalpais College is the outgrowth of a nearly 25-year-old college program serving students in California’s oldest prison. It was formally accredited as a two-year college last month by the Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges and became the only accredited, independent liberal arts college in the country that operates its main campus out of a prison, according to college leaders. Mount Tamalpais offers a general education associate degree program and a college preparatory program that teaches students writing and math skills. The faculty members are entirely volunteers, many of them from local colleges and universities, including the University of California, Berkeley, and San Francisco State University.

The college serves about 300 students at a time, which is a small portion of the 3,049 inmates housed at San Quentin. Enrollment is capped at around 300 because of limited classroom space. At least 3,731 students have taken courses through the program over the years.

Jody Lewen began volunteering as a graduate student at the program in 1999 and is now the college’s president. She said the idea of becoming an independently operated and accredited institution started out as a pipe dream. The program was formerly known as the Prison University Project and began as an extension of Patten University, a private Christian institution in Oakland, which became an online, for-profit university.

Lewen wanted the college to stand on its own, without its success contingent on a partner institution.

“I had fantasized about that for a long time,” she said. “I just thought it would be really extraordinary to be independent, but it never seemed like there would be any way we could pull it off financially. Just the logistics and the infrastructure required seemed so daunting at the time.”

She still worries about finances—Mount Tamalpais is funded by private philanthropy, so classes, textbooks and supplies are provided to students for free—but she got her wish for the program to strike out on its own and provide a level of quality that matched colleges outside the prison.

“Making the decision to become accredited meant that we would be held to the same standards as main campuses typically are, as schools as a whole are,” she said. “We were going to have to answer to all these questions about access to technology, library resources, data collection and analysis, all of the substance of accountability … It just ended up being incredibly productive for us.”

She emphasized that the accreditation will ensure the long-term stability and quality of the program and also will send a larger message.

“What we hope is that our coming into being as a college that happens to be located in the prison has the effect of drawing the attention of the higher education community to those students and causing them specifically to recognize incarcerated students as a part of the higher education community,” she said.

The accreditation comes at a time when lawmakers and higher education leaders are increasingly focused on expanding college opportunities for incarcerated students after Congress in 2020 overturned a 26-year ban that denied incarcerated students access to the Pell Grant, the federal financial aid program for low-income students.

Second-Chance Pell, a pilot program established in 2015, originally allowed 67 select institutions to offer prison education programs with the support of the Pell Grant. The pilot is expected to expand to up to 200 colleges and universities in the 2022–23 award year. The federal funds will be widely available to incarcerated students starting next year.

Incarcerated people tend to have lower levels of education compared to the general population. A 2018 report by the Prison Policy Initiative found that a quarter of formerly incarcerated people never graduated high school. This population is almost twice as likely to lack a high school degree compared to American adults at large. Meanwhile, more than half don’t hold credentials beyond a high school diploma or GED.

Research shows prison college programs have wide-ranging benefits for incarcerated students. Incarcerated people who participate in college programs have a 43 percent lower recidivism rate than their peers, according to research from the Bureau of Justice Statistics. Only 14 percent of incarcerated people who earn an associate degree and 5.6 percent who earn a bachelor’s degree return to prison.

Shannon Swain, superintendent at the Office of Correctional Education for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, said these programs also increase morale among the incarcerated.

“I can’t overemphasize the positive effect that all college programming has on the institutions,” she said. “It’s just really amazing, because all of the sudden, you have incarcerated folks that are more mature, they’re focused on their own recovery, they’re focused on their future, and it influences the people around them.”

The news of Mount Tamalpais’s new status has been widely celebrated by San Quentin staff.

“The accreditation of Mt. Tam as an independent college represents years of dedicated service in helping an underserved segment of our society,” Ronald Bloomfield, warden at San Quentin, said in a press release. “The students of Mt. Tam experience an amazing high-quality education. Graduates leave the college with knowledge and skills essential to becoming productive citizens. With an increased worldview comes increased possibilities and hope for a better future.”

Sam Robinson, public information officer at the prison, said one of the “hallmarks” of the prison is that students can leave with a free associate degree, and the program has led many people to request to transfer to San Quentin.

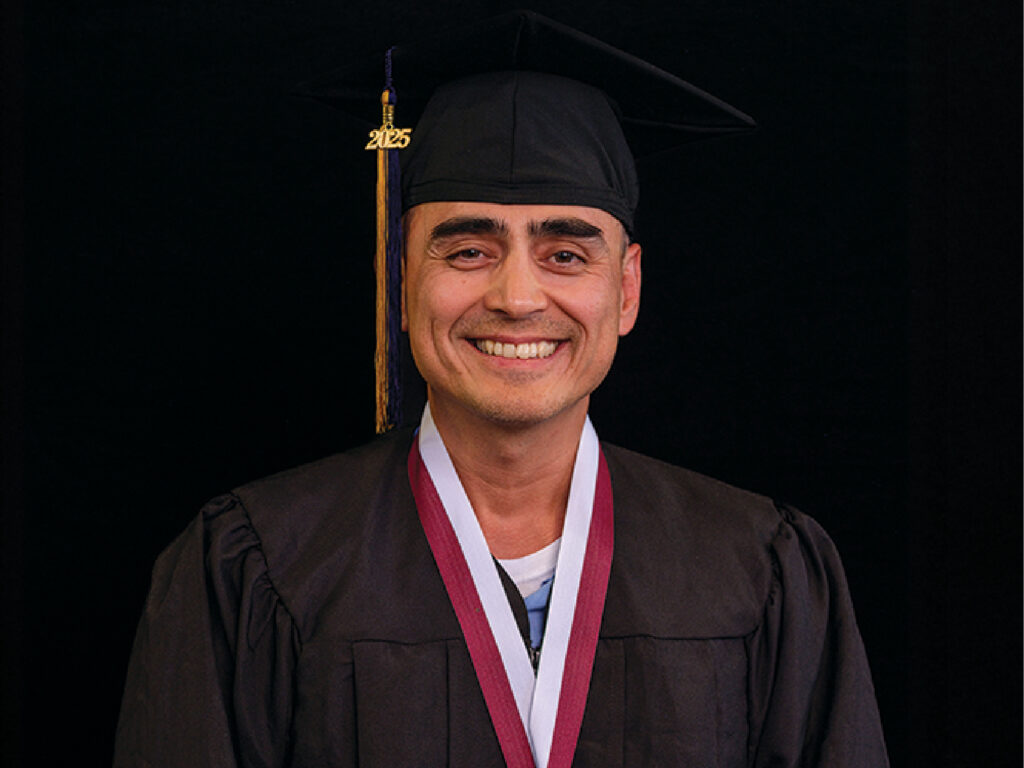

Corey McNeil, who graduated from the college in 2019, was among those students. He said he came to prison with a middle school education, and when he was first incarcerated, he decided to further his education to show his family he was on a “different trajectory.” He earned his GED at another prison before he requested to transfer to San Quentin to go to Mount Tamalpais because of its reputation for face-to-face learning with instructors and robust classroom discussions. McNeil earned his general education associate degree while simultaneously working as a clerk for the program for four years. He became the college’s alumni affairs assistant after his release last May.

McNeil recalls having lively discussions in the prison yard, ranging from the Reconstruction era in U.S. history to the pros and cons of utilitarianism, with his classmates, whom he now considers “lifelong friends.” He made regular calls to his mother and uncle to tell them about classes and update them on his academic progress.

“Now to see that MTC is growing and achieved accreditation, it feels like not only a celebration of the college’s accomplishments … as an institute of higher learning, but the accreditation also feels like an acknowledgment of all the hard work that the students themselves have done as well,” he said. “It’s like the college’s success is our success, our validation.”

Monique Ositelu, a higher education senior policy analyst at New America, a liberal Washington think tank where she conducts policy research related to prison education, said accreditation may also assuage concerns students have about the value of their degrees.

She noted that the number of higher ed programs in prisons dwindled after congressional lawmakers banned the use of Pell Grants for incarcerated students, and the remaining programs were typically privately funded by organizations or philanthropies. However, not all of these long-standing private programs were accredited, even though degrees from accredited institutions hold “a little bit more weight” with employers and four-year universities where students may hope to transfer, she said.

A student she interviewed at San Quentin once told her he worried future employers wouldn’t respect his degree.

“Will they see it as a degree or a prison degree?” he asked her.

Other students expressed “a lot of faith that this degree will outweigh that they served time in prison,” she said. “We owe it to them as educational providers to ensure that it does, and one of the ways to go and do that is through accreditation.”

She also pointed out that now that the Pell Grant will be widely available to incarcerated students starting in 2023, students can take developmental math and writing courses or earn associate degrees at Mount Tamalpais for free and save their Pell dollars to pursue a bachelor’s degree, which makes a four-year degree more affordable.

College-in-prison experts believe Mount Tamalpais would be a difficult model to replicate at other prisons. Swain, of the Office of Correctional Education, believes the college has flourished in part because of its location. San Quentin is located in Marin County, a short driving distance from many colleges and universities, unlike the majority of prisons, which are located in rural areas.

“Try to find a faculty member that’s qualified and interested in teaching statistics in a prison in Susanville [Calif.]—it’s not an easy thing to do,” Swain said.

She noted that San Quentin offers hundreds of educational and recreational programs, and the prison is such a popular place to volunteer in the surrounding community that it has more volunteers than incarcerated people. The prison is also at a Level II security status, which means most of the prison population can move around freely for most of the day, which she said makes it easier to provide programs.

Even if Mount Tamalpais remains an outlier as an independent, entirely in-prison college, Lewen still believes its accreditation can jump-start a broader discussion about ensuring prison higher ed programs offer value.

“One can do this work well without being an independent college, and there are some very strong in-prison higher ed programs that are extension sites,” she said. “My hope is not necessarily that lots of independent colleges in the field sprout up but that we are able to spur conversations about quality and what’s going on in those programs in a way that benefits the students.”

Ositelu also emphasized that quality prison education programs can have ripple effects on whole families and communities by building up incarcerated students’ confidence before they re-enter society, making it easier for them to secure jobs after release and motivating future generations to pursue higher education.

A degree “signals to the market that they can do the job,” she said. “They have the skill set to do it. They have the content knowledge to do it.” But a college education has “an impact greater than the degree. It has an impact on who they are, on their family, on their children.”

Attribution: This article originally appeared in Inside Higher Ed on February 8, 2022.