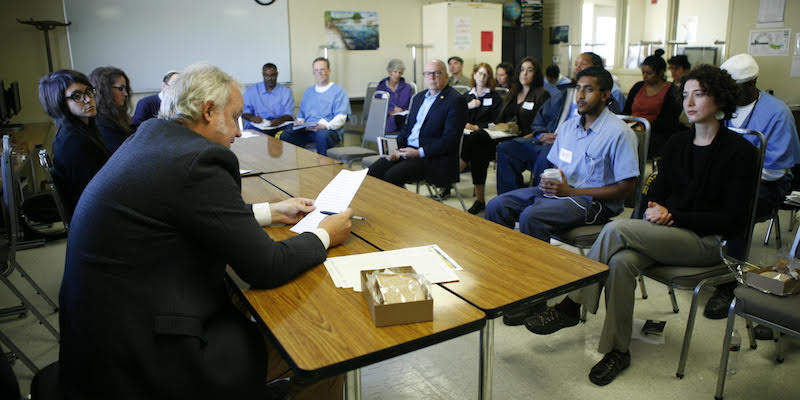

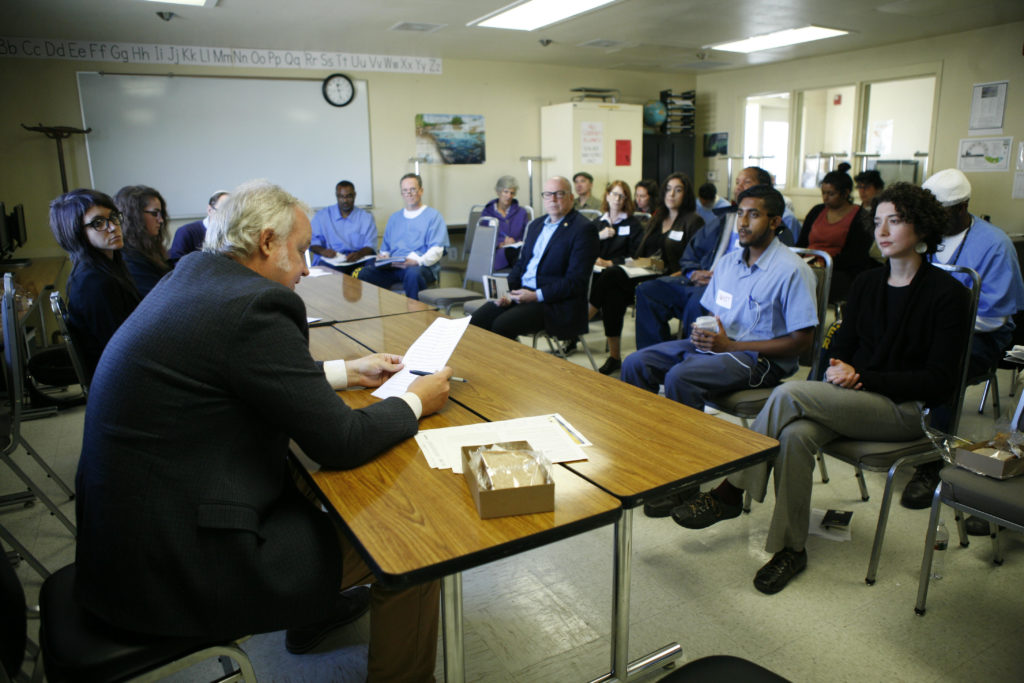

On October 5, scholars from across the United States convened to engage in dialogue with the Prison University Project’s students at San Quentin State Prison. As one of the first academic conferences held inside a prison, “Corrections, Rehabilitation, and Reform— 21st Century Solutions for 20th Century Problems” allowed those most impacted by America’s carceral system to contribute to the conversations that shape their own lives and futures. In our current era of mass incarceration in which racial and economic injustice are the prime contributors to prison overpopulation, the Prison University Project and our students see new modes of thinking about criminal justice as imperative to dismantle the systems of oppression that are structurally embedded in America’s social and political institutions.

Along with the Prison University Project staff, a committee made up of incarcerated students did all of the planning, decision-making, and coordinating for the conference. We received nearly 100 paper submissions and had over 30 scholars ultimately participate in nine panels throughout the conference’s two morning sessions. Panel topics included “Bodies and Control,” “Histories and Narratives of Incarceration,” “Alternatives to Incarceration,” and “The Fine Line Between Help and Harm.”

Some highlights:

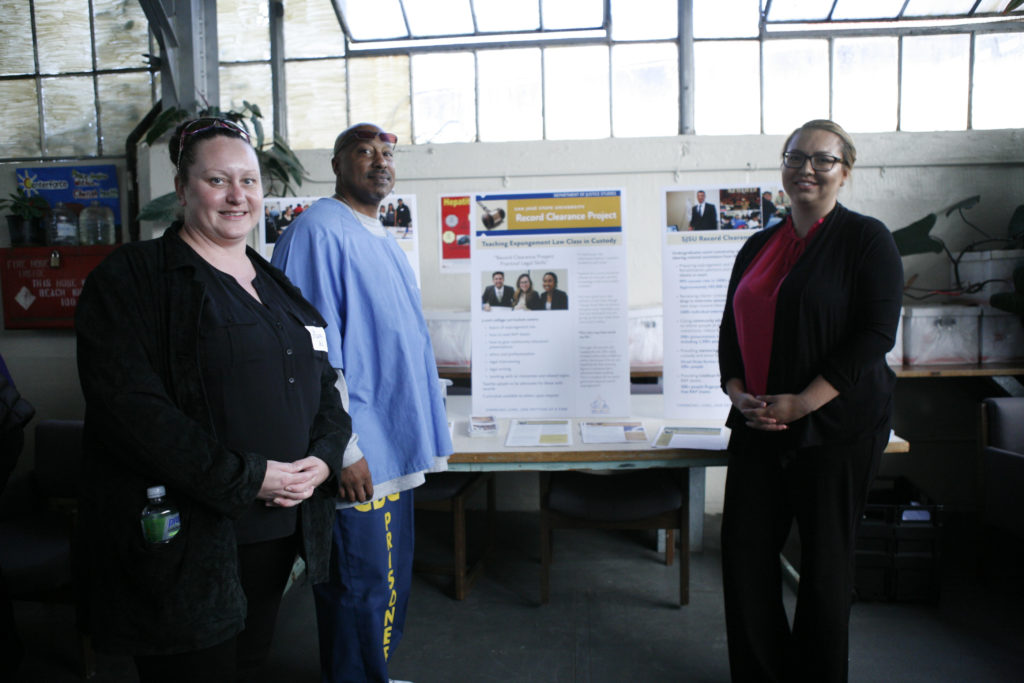

- Romarilyn Ralston of Project Rebound shared her journey from incarcerated black woman to free scholar and activist and provided an intersectional analysis of the unique challenges women face in prison. Often overmedicated, forced to deal with the horrors of pregnancy and childbirth while a subject of the state, and overwhelmingly incarcerated as victims of domestic violence and sexual abuse, women and their experiences must be centered as we engage in conversations of reform and abolition.

- Farah Godrej of UC Riverside problematized yoga and mindfulness training in prison by asking if techniques for docility and acceptance work to maintain the status quo through complacency or subvert it.

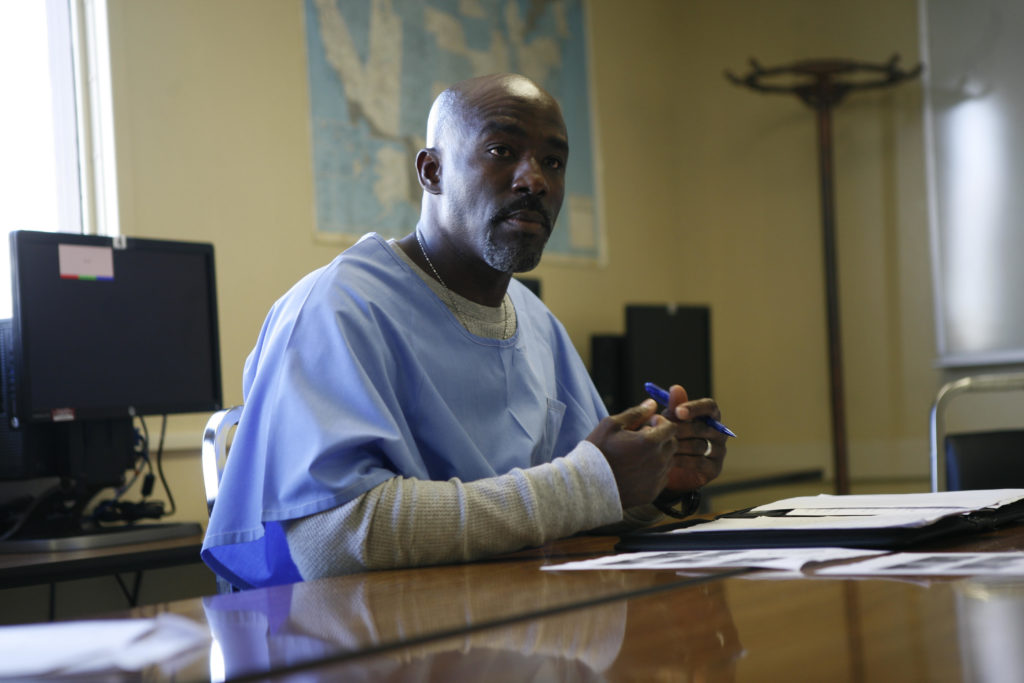

- Incarcerated scholar and Prison University Project clerk James King and Prison University Project’s program administrator Heather Hart co-presented a paper on the savior complex that asked practitioners to critically engage with their own identity, privilege, and motivation for working in a prison. Not doing so, Heather and James argued, leads to practitioners inadvertently reproducing structures of inequality and power imbalances they believe they are working to break down.

Though panelists came from a wide array of lived experiences, backgrounds, and academic disciplines, a number of connecting themes emerged as throughlines from their remarks. All participants found centering and amplifying incarcerated voices as the most important first step to building a movement. Most saw higher education in prison as a radically inclusive alternative to punitive methods of corrections that instead offers humanity, dignity, and opportunities for healing and growth. Disrupting traditional binaries of “inside/outside” and “incarcerated/free,” this project of higher education in prison must be conducted in collaboration as practitioners and students co-create educational environments and engage in mutual learning.

Scholars across the board also agreed that as Americans living in the 21st century, our fates are intimately intertwined—we all suffer under a carceral state that destroys individual lives, families, and communities at large. Our current system of criminal justice serves to perpetuate inequality by criminalizing the actions of certain populations while those responsible for a staggering degree of social harm remain on Wall Street, in the White House, and other halls of power. Incarcerated and free scholars grappled with larger questions of state-sponsored suffering, education, and societal transformation: whose trauma is criminalized and whose trauma is normalized? How is education tied to power and social control? What does a world without prisons look like? And how can incarcerated people best leverage their experiences to lead a movement for change?

Panelists were joined by the Prison University Project staff, board members, volunteers, donors, and other higher education in prison practitioners. We were fortunate to also welcome Florida State Representative David Richardson.

“It was my pleasure to attend the recent academic conference hosted by the Prison University Project. As a Florida State Representative, I have pursued prison reform initiatives in the State of Florida over the past three years. Most of my work has been at the ‘micro’ level with much of my time being spent on the details of prison operations. It was very beneficial to hear the discourse from a ‘macro’ perspective. I learned so much, and it was especially beneficial to have the conference held inside a prison facility so inmates could have their voices heard.”

-David Richardson, Florida State Representative, District 113

The conference closed with a rousing keynote address in San Quentin’s chapel from Patrick Elliot Alexander, Associate Professor of English and African American Studies at the University of Mississippi, co-founder of the University of Mississippi Prison-to-College Pipeline Program at Parchman/Mississippi State Penitentiary, and author of “From Slave Ship to Supermax: Mass Incarceration, Prisoner Abuse, and the New Neo-Slave Novel.” Echoing remarks of past reformers and abolitionists such as Martin Luther King Jr, Angela Davis, Fannie Lou Hamer, and Malcolm X, Professor Alexander offered a scathing indictment of America’s systematic disenfranchisement of black bodies and celebrated the liberatory potential of higher education in prison as a means for social justice. In one particularly powerful moment, Professor Alexander had the audience acknowledge the deep intellectual capacity of everyone in the room by having us shout together, “I am a student! I am a teacher! I am a scholar! I am capable!” These words reverberate loudly beyond the walls of San Quentin as we move toward a future where brilliant minds behind bars are increasingly celebrated and serve as active participants in dialogues about criminal justice rather than objects of discussion.

The Heising-Simons Foundation provided funding to produce a short documentary about the conference shot by R.J. Lozada (top of page). Photographs by Prison University Project student Eddie Herena.

Please note that the Prison University Project became Mount Tamalpais College in September 2020.