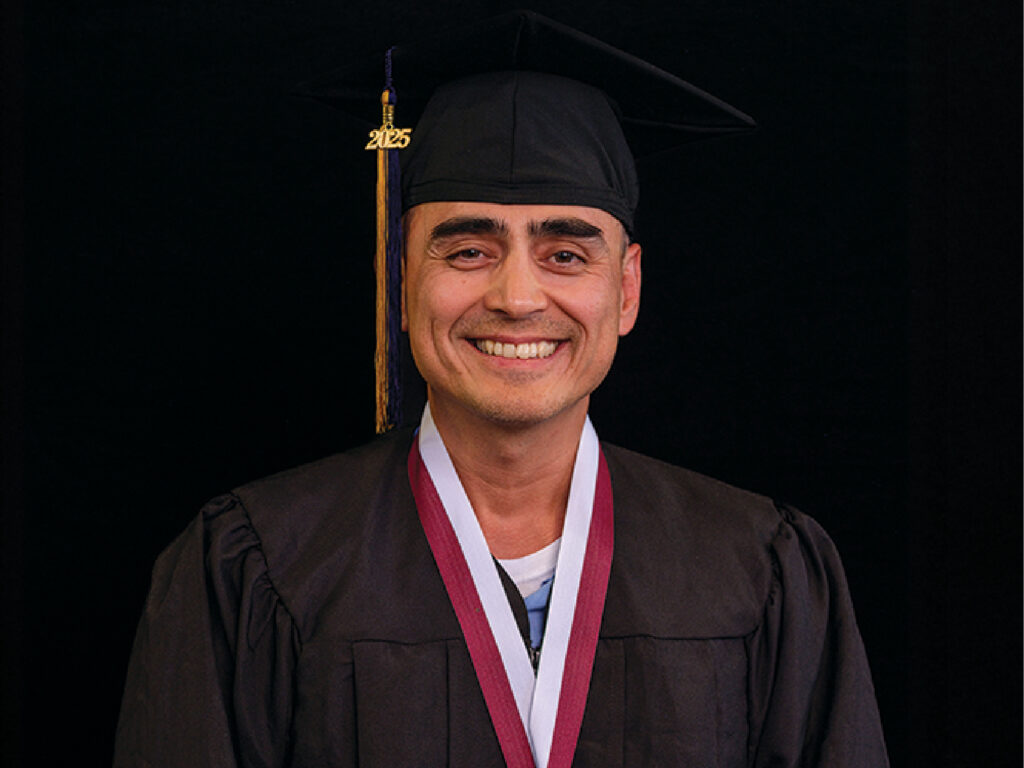

Former Prison University Project student and former San Quentin News editor Jesse Vasquez was featured in The Atlantic.

Jesse Vasquez first heard about the Homecoming Project while working as the editor of the San Quentin News, an inmate-run newspaper in California’s San Quentin State Prison. Impact Justice, an organization focused on criminal-justice reform, had set up a small program that was recruiting homeowners to open up a room in their house to someone coming out of prison—like Airbnb, but for people who had most recently lived in a cell. He’d never heard of anything like it: strangers, opening their homes to people convicted of felonies and helping them get back on their feet?

The 36-year-old Vasquez had been incarcerated since the age of 17, and was sentenced at 19 to multiple life terms for an attempted murder in a drive-by shooting in Orange County. He thought he might never get out. Then Jerry Brown, California’s governor at the time, commuted his sentence, allowing him to seek parole far sooner than he’d expected. In February 2019, Vasquez’s parole was granted. But where would he go, he thought, and how would he rebuild a life? Then he remembered the Homecoming Project. Impact Justice, he recalled, acted as a matchmaker between a host and a tenant. The organization paid for the first six months of rent, offered the newly released person training and case management, and provided support to the host. That sounded good to Vasquez. He sent in his application.

About three weeks later, Vasquez received a written response from Impact Justice: He was in. The program’s coordinator, Terah Lawyer, had a list of three prospective hosts. He hit it off immediately with the second. Candi Thornton, originally from Florida, was in her early sixties. She was a church leader, ran volunteer programs and charity drives, and managed an assisted-living home in East Oakland for people with disabilities. She had already hosted someone through the Homecoming Project. If he lived with her, she told him, he could join her at church, share a meal from time to time, and call on her for advice. “For me,” she told Vasquez, “it’s all about faith and community.” That sold him. He’d become a devout Christian while in prison, and he could hear the care in her voice, like she wanted him to succeed. They were a match.

It just so happened that Thornton was out of town when he was released, on a sunny morning last May. So, the next day, after Vasquez met with his parole officer, Lawyer took him to Thornton’s house to show him around. It was a big sherbet-pink house on a quiet street off of the 580 freeway in East Oakland, at the base of the nearby wooded hills. The house had a small downstairs apartment with a separate driveway and entrance. It had two bedrooms, one for Vasquez and one for the existing tenant.

The apartment had a kitchen, living room, and couch; there was also a weight-lifting kit, a large television, and a coffee table. The roommate, a trim, tattooed 50-year-old man named Mike Davis, also formerly incarcerated, was on his way out. Thornton had explained the Homecoming Project to him, and he greeted Vasquez warmly. “You need anything,” he said, “you just let me know.”

After everyone left, it was just Vasquez and his apartment and his own set of jangling keys and the vast quiet of the residential street. He closed the door and stayed up nearly the whole night, unable to sleep because of what a good and terrifying feeling it was to be free.

Vasquez didn’t realize, quite yet, how lucky he was. The Homecoming Project had been launched as a pilot, and he was one of only a dozen or so who had been accepted, out of several hundred applicants. Lawyer had chosen him because of all his activities during his life inside—men’s groups, mentorship programs, the paper, college classes. He had even earned an associate’s degree. “If a person can accomplish all of that positivity with so little,” Lawyer said, “imagine what they could do with a little bit of support and encouragement.”

The truth was that the Homecoming Project had a lot riding on Vasquez, too. The funding for the project covered only the pilot phase. To keep it going, they had to convince funders that it worked—that it wasn’t wasted on Vasquez and others in his position. In the conservative culture of criminal justice, private and public funders can be wary of funding experimental programs. “Any new project that is against the norm comes with a lot of risk,” explained Alex Frank, a project director at the Vera Institute of Justice. Nonprofits must meet strict qualifications to be considered for state and federal funding (and are entirely ineligible for some grants); as a result, the same organizations and for-profit businesses tend to be funded again and again, a pattern that doesn’t lend itself to new ideas.

While foundations and private donors are generally more open to innovation, the individual grants are usually smaller, and funding often only lasts for a few years—just long enough to get a program off the ground, but not enough to make it last or bring it to scale. Yet in a country with more than 2 million incarcerated people—a population that states and the federal government are desperate to reduce—the need for innovation is urgent, particularly when it comes to improving outcomes for people who have been released.

Operating in Oakland, where Silicon Valley’s influence is deeply felt, the advocates at Impact Justice had been working for years, against difficult odds, to bring a more innovative approach to criminal-justice reform. In 2015, Alex Busansky, an attorney and Impact Justice’s president, was talking to colleagues about the lack of supportive housing options for people getting out of prison.

Upon leaving prison, he felt, people don’t just need a place to sleep; they need a home—a place where they are cared for and feel they belong—and connections to a positive community. They need to feel welcomed back into society and to have a sense of agency. As Lawyer put it, “People don’t realize that in the way it’s currently designed, they are still ostracized from society, and they are having to fight to get back in.”

Finding housing, especially in California, is the most immediate problem and often the hardest to overcome. Vasquez could hardly have picked a more challenging place to try to rebuild a life. As of November 2019, Oakland had the fourth most expensive rental market in the United States. San Francisco had the most expensive rentals.

Former prisoners are often ineligible for subsidized housing, and finding an affordable place of one’s own from inside prison is nearly impossible. Money is a huge obstacle, of course, but the main issue is having a criminal record: Landlords frequently ask about a potential renter’s prior convictions, and some require background checks.

On top of that, people being released on parole or probation must have their post-release housing arrangement approved by their parole or probation officer. It has to meet a number of requirements, some of which pose serious barriers for recently released inmates. A parolee or probationer often cannot, for example, live with a person convicted of a felony, and a parole or probation officer can nix any housing arrangement that they deem insufficient or a threat to good behavior. (Vasquez said his parole conditions don’t prevent him from living with someone with a criminal record.) In many cases, none of the residents of a house can have been codefendants, witnesses, or victims of the crime for which the parolee served time, and a place where people are known to abuse drugs or alcohol is immediately nixed as too risky. Some parole officers will check to see if the police have responded to calls from or about the residence.

Halfway houses are an option, but they have limited availability. In many cases, they mimic some aspects of prison, with strict regulations restricting residents’ freedom: curfews, required drug testing, unannounced visits from parole officers, restrictions on travel. They are often on the outskirts of communities, far from resources like libraries and banks, as well as the places that people returning from prison need to rebuild their lives, such as the Department of Motor Vehicles, the Social Security office, and hospitals.

A 2016 study by the University of Michigan’s National Poverty Center showed that parolees move an average of about once every five months, compared with the U.S. average of once every five years, and the less money and fewer social connections they have, the more they move. (Formerly incarcerated people are also 10 times more likely to be homeless than the average population.) All of this conspires against people coming home from prisons to make it more likely that they will have inadequate housing—and, in turn, will end up back inside. According to one study, 83 percent of state prisoners across 30 states were back in prison within nine years; in California, about half of those released from prison end up back in prison within just three years. Numerous nation- and statewide studies show that the availability of stable, affordable housing helps determine whether someone ends up back in prison.

When Impact Justice’s Busansky and his colleagues tried to brainstorm how they might come up with housing options for people released from prison, he brought up Airbnb. They joked that all they needed was enough money to pay for nightly Airbnbs for all the returning people in need of homes. But that gave Busansky an idea: What if people opened up their spare rooms to people coming out of prison?

In 2017, following Donald J. Trump’s inauguration, one of Impact Justice’s funders, the Emerson Collective (which owns a majority stake in The Atlantic), sent around a request for proposals for projects promoting justice and unity, and Busansky applied to start a pilot for the Homecoming Project, aimed at securing housing for 50 people over two years (though that goal was eventually lowered to 25 people). He got the grant and hired Terah Lawyer to launch the program. Lawyer was committed to prison reform and social justice and had herself been incarcerated for 15 years; she knew more than most people the perils of rebuilding a life after prison.

Jesse Vasquez is toned from daily workouts, a habit he developed in prison; he has a close-shaved head, a boyish grin, and a poised, determined manner. On his first morning in Thornton’s house, he went shopping for proper bedding with Sam Johnson, the Homecoming Project’s community navigator, and Johnson’s wife. They walked up and down the sheet aisles of the San Leandro Walmart, looking at all the options. “Pick what you want,” Johnson said—the Homecoming Project would pay for it—but Vasquez couldn’t choose. He didn’t want to be greedy, and he was overwhelmed by having any choice at all.

“I already have a big old bed,” he said. “It doesn’t matter to me.”

Johnson understood. He had been locked up for twenty-six years before being released two years earlier.

“Just pick the one you like,” he told Vasquez. “Pick anything at all.” Vasquez settled on a navy-blue comforter, solid on one side, striped on the other, that suited him well enough: It was manly, he thought, but with some style. That weekend, he and Thornton spoke on the phone.

“This is your home,” she told him. “Don’t you forget it.”

Thornton had returned from vacation, and Lawyer arranged a meeting at the Impact Justice office downtown. Thornton is a bit shorter than Vasquez, with a wide, kind smile and freckles dotting her cheeks. “I can do yard work,” he told her, wanting to offer something in return for her hospitality.

“Don’t worry about that,” she said. She already had a guy who came twice a month. They signed the paperwork, and Lawyer snapped a picture of them.

Later, driving home, Thornton turned to him. “You let me know what you need,” she said. “I’ll get it for you, and if I can’t get it for you, I’ll find someone who can.”

When Vasquez had moved into his bedroom, there was already a bed frame, a box spring, a mattress, a small white desk with drawers, and a closet with hangers. He had only a few items of clothing, so Thornton helped him find some donated suits and dress clothes, which he hung neatly in his closet alongside his exercise and casual clothes. He bought a steamer to keep everything fresh and wrinkle free. He and Davis had only one pot between them; Thornton went out and bought them a new set of pots and pans. “You need to eat,” she said.

Vasquez moved the bed from alongside the window and pulled it off the bed frame so it sat lower than the window’s ledge; where he’d grown up in Los Angeles, there were enough drive-by shootings that people knew to keep their bed below window level, lest they be hit in their sleep. He situated the desk right next to a window overlooking the gated parking area and the yard with a plum tree, an acacia, and a fig. There was a resident squirrel, too, that he liked to watch dash around the drying grasses and up into the trees.

Dealing with a housemate wasn’t as hard as he had expected. The apartment he shared with Davis, he estimated, was about five times the size of his cell; in prison, he’d had plenty of experience getting along with people in much tighter quarters. Davis was cool, and with their busy schedules, and the fact that Davis spent a lot of time with his girlfriend, Vasquez hardly ever saw him, which suited them both just fine.

One night a few weeks after he was released, Vasquez was home alone. He texted his brother from his room.

“What’s the weather like up there?” his brother asked.

“No idea,” Vasquez wrote back. “I’m inside.”

“Why you inside, stupid? Go outside and take a look around.”

Go outside, at night, by himself? He was used to being indoors, cell gates closed and locked. He opened the door, stepped into the evening air, and sat in a chair across from the plum tree. Dusk settled onto the hills across the highway. It had been a sunny day, and it was a clear night, and here he was, sitting outside a house of his own. He took pictures of the hillsides and the sunset and sent them to his brother.

“Nice,” his brother wrote back.

Vasquez’s room, with its little white desk, became his headquarters: Each morning around 4:30, he’d wake up, make a list of what needed to be done that day, and map his goals for the rest of the week. He’d start sending emails and setting up meetings—informational interviews with journalists, conversations with educators about working as a mentor or speaking at a conference. Vasquez envisioned his home like one of those paddles attached to a ball with a rubber band: You could stretch out from there, knowing you had a place to return to. From there, he could plan everything else—getting a California ID and a birth certificate, applying for Medicaid, opening a bank account. Johnson was his personal reentry assistant, helping keep track of what needed doing and texting him reminders: “You take care of that yet?”

It wasn’t just the big stuff that confounded Vasquez, like how to get a job or get over the paralyzing fear of a cop car driving by. (“Does it still bother you?” he asked Johnson once.) More often than not, it was the smaller stuff on which he needed advice. How much milk are you supposed to buy, and when does it go bad? What do you cook for dinner—how do you cook at all? How do you make sure the produce you pick up at the store—with such good, healthy intentions—doesn’t rot in your fridge? In prison, everything had a long shelf life; you could buy a can of soup and keep it for years before heating it up and slurping it down for dinner. But groceries on the outside spoiled so quickly.

Vasquez didn’t even try to cook at home until three weeks in. He had bought himself some bacon and eggs at the store. Growing up, his mom had cooked for him, and he’d only really known how to boil an egg. But eggs and bacon, he figured, couldn’t be that hard. He separated the bacon strips onto a frying pan and cracked a few eggs. Things were going well enough, but the bacon started to smoke a little, and then a lot, and all of a sudden an alarm began sounding from what seemed like every room in the house.

The alarm in Thornton’s house didn’t just sound; it spoke. “There is a fire in the building,” it announced robotically. “There is a fire in the building.” This repeated again and again, alongside a terrifying, continuous beep. Vasquez had seen on TV how police and fire trucks arrived on the scene during alarms like this. Just what he needed, he thought, a police contact that could affect his parole. The smoke was collecting. The alarm wouldn’t stop. He turned off the stove, opened the doors and windows, prayed for the smoke to go away, and then began fiddling with the smoke detector until the thing finally quieted. He threw his half-cooked bacon into the trash.

“I almost burned the house down,” he confessed to Thornton later, panicked and apologetic.

She asked him what had happened, and when he told her, she just laughed. “Don’t worry,” she said. “Just turn on the vent.” She explained how it worked and where to find the button.

A typical housemate, having taken a risk letting a parolee live with her, might well have balked at this. Thornton encouraged him to try it again. He began Googling recipes and watching cooking shows on YouTube, mimicking the professionals’ moves as he worked his way through his kitchen, trying not to set the house on fire.

The people behind the Homecoming Project see its cost as one of its main selling points. The program spends about $10,000 for each six-month stay, including rent, training for hosts, and case-management costs. A spokeswoman for the Bureau of Prisons said that in the 2018 fiscal year, the average cost of caring for an inmate in a federally contracted reentry center (or halfway house) added up to about $17,246 for the same amount of time—though she warned that it’s difficult to make a direct cost comparison between programs that may be very different.

A less tangible benefit is the informal social networks that participants like Vasquez build through the program. To recruit its hosts, Impact Justice stages presentations at churches and local organizations. Once people apply and are properly screened, Lawyer begins the matching process, as she did with Thornton. Then the hosts attend several evening trainings, where they are immersed in statistics related to the school-to-prison pipeline, recidivism rates, the needs of people returning from prison, and former inmates’ reactions to freedom.

Case management is a central part of the Homecoming Project; the to-do list of people getting out of prison can be so long and daunting, it can bury them. Without a driver’s license, a Social Security card, access to the internet, a bank account, or an understanding of public-transportation lines, it’s nearly impossible to set up a straight life. The Impact Justice team understood that asking the Homecoming Project hosts to shoulder these responsibilities could overwhelm them, as well. (As nonexperts, they could also go about things wrong and inadvertently end up doing more harm than good.) Both hosts and tenants know that if something goes awry or some need arises, they can call Johnson.

The Homecoming Project is designed to last for six months. That’s how long Impact Justice pays the rent, and how long participants like Vasquez get their formal case management. The idea is that after this softened, supported landing, a person like Vasquez will be ready to be on his own—or closer to ready, anyway.

Where Vasquez decides to live after his six months in the program is his choice, and, to some degree, his host’s. If the relationship is working, Lawyer encourages them to continue to live together (an arrangement that not only offers the comfort of continuity, but often costs less than the market rate). Vasquez’s six months are up at the end of this month, and he plans to keep living in Thornton’s apartment; for her part, she’s glad to have him. They’re drawing up a lease of their own.

Sarah Gillespie, a researcher at the Urban Institute focusing on the link between homelessness and recidivism, noted that, among all the people being released from prison, those selected to participate in the Homecoming Project are less likely to end up homeless anyway; they have, in a sense, been hand-picked for success. All Homecoming Project participants are selected based on their hosts’ abilities to support them, meaning they may be less likely to have serious physical disabilities or complex mental-health challenges, for example, which would also create a more complex set of barriers to transitioning back into society. Bridge programs such as this project, Gillespie added, often focus on the months just after reentry, sometimes at the expense of long-term benefit.

So far, though, the Homecoming Project has succeeded in both the initial six-month period and beyond. Since the program began in August 2018, none of the first 14 participants have ended up back in prison. All of them are housed and either gainfully employed or enrolled in school. The 15th participant was released from prison this month. The project remains an experiment, however, with a tiny sample size. Busansky and Lawyer are hoping to scale it, first in neighboring Contra Costa County and then statewide. But their funding is running short.

Lawyer feels that she and her colleagues have found a solution to an intractable problem: how to improve the way in which a community relates to its members who are returning after being incarcerated, while keeping people from returning to prison, with an approach that is both effective and affordable. Lawyer said that, through the Homecoming Project, participants like Vasquez “are really able to ask themselves, ‘If I had all my needs met, what would I do with my time?’” She, Busansky, and Johnson are proud of the support they’ve been able to give 15 people in just a little over a year, but the impact will continue to be minuscule unless they can significantly expand the program.

Lawyer and her colleagues have secured some additional funds since their initial grant, though not enough to start up a new class of participants. They’ve largely tried for private funding, but have found that foundations focused on the reentry population hesitate to fund housing initiatives—they’ll tackle training and job readiness, for example, but rentals are just too expensive and the need for homes too vast. The project’s coordinators have struck out on public funding, too. In November 2018, they applied for a $3 million grant for rental assistance from California’s Board of State and Community Corrections, with an application connecting the dots between the post-incarceration period and homelessness. In late August, they heard that their application was denied.

Another challenge with securing funding for programs like this one, in the view of Maureen Vittoria, Impact Justice’s chief operating officer, is that when a project attempts to radically change the way things are done within an entrenched system, decision makers inside that system are loath to take a chance on funding it—or to even acknowledge that the status quo is flawed to begin with.

Vasquez noticed that Thornton’s otherwise tasteful, tidy, dust-free house was often strewn with boxes. About a decade ago, Thornton launched a partnership with the Alameda County Community Food Bank. Nearby mega-stores, like Target, Walmart, and Costco, would set aside their recently expired or damaged food, and a team of volunteers would pick it up and distribute it at community sites. Over time, the operation grew, and they needed more and more volunteers. Now, Vasquez started helping out, volunteering each Monday for food pickups and setting up for events like Taco Tuesday. Thornton and Vasquez also went to church together every Sunday, and Vasquez started driving people there on occasion.

It was easy for Vasquez to feel like he’d been on a storage shelf for 19 years, collecting dust. He couldn’t make up for being gone, but staying and working with Thornton felt like being mainlined into a sense of purpose. Lawyer had helped Vasquez get an unpaid internship at an organization devoted to criminal-justice reform called the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights. Some teacher friends whom he had met while in prison would take him places like the beach in Marin, and they were preparing a paper for an upcoming conference about the school-to-prison pipeline.

Between this and his work with the food bank, Vasquez’s calendar was packed with meetings. He continued to wake up each morning at 4:30; his to-do list got longer, his calendar more full. Every morning, he took a timed six-minute shower: In prison he’d had five minutes, so he allotted himself an extra minute now that he was free. He was often out the door by eight or nine o’clock.

As a matchmaker, Lawyer knew that every roommate pairing was different. She had worked with one former inmate who had grown up in a volatile household. He now lived with a couple who cooked dinner every night and argued amicably about world affairs, showing him what a healthy relationship could look like. Another participant had been homeless for nearly a year after he’d been released from prison, and for him, living inside a home with others had been all about rebuilding his ability to trust.

Vasquez is a doer, a go-getter. A physical home was an important foundation, but he’d been looking for a broader sense of home—a meaningful place in his community, a feeling of being able to influence others and pursue opportunities. With Thornton, he’d found it.

One day, as Thornton was coming home and Vasquez was heading out, he mentioned his six-minute shower allotment. “You don’t need to time it,” she said to him. “No need to rush it. Just take your time.” Vasquez started giving himself a few more minutes in the shower.

Though new admissions to the Homecoming Project have stalled, Lawyer and her colleagues believe so strongly in it that they are now trying to support similar programs elsewhere—even if they are run by different organizations. They are developing a tool kit and a technical-assistance service so that they can help other organizations hoping to start something similar in their own communities.

Lawyer and Vittoria explained that they are going to start looking into private funding again, while also trying their hand at government funding, however much of a reach that may be. They continue to hope that state and federal officials will remain open to experiments like theirs. Until then, they’re soliciting more private donations and stuck in somewhat of a holding pattern. There are more than 100 applications stacked on Lawyer’s desk and, until there is more funding, zero spots for them.

Vasquez wanted to start working with kids who are struggling in school to offer them the guidance he wishes he’d had when he was their age; he applied to be a volunteer in the Oakland Unified School District. He was cleared, and began volunteering this month. He got permission from his parole officer to go to Sacramento in August, too, to lobby with the Ella Baker Center. He wore one of the suits Thornton had gotten him and spent the day speaking with policy makers in the scorching Sacramento heat about injustice in the prison system: price gouging at the commissaries, unaffordable co-pays to visit a clinic, phone companies preying on inmates’ desperation to speak to people on the outside.

When he got home, he told Thornton all about it.

“I’m so proud of you,” she said. “You’re going places. You are.”

One day Vasquez hopes to shake off his identity as a formerly incarcerated person, to not be seen as a parolee or a “returning citizen.” He just wants to be a regular guy. He feels good volunteering on the food drives, with Thornton directing him and the other volunteers: yogurt over here in the shade, meat on this table, fruit in these bins.

Sometimes, the feeling of usefulness comes with a shadow. If he hadn’t been locked up, Vasquez could have been helping others all along. Now that seems like wasted time. He feels like this at other times, too, like when he goes hiking—something he likes to do a few times a week on the network of trails circuiting the Oakland and Berkeley hills—and sees something astounding, like a stream flowing down along the trail beneath a dome of tall trees. How nice it is, he thinks, to be able to see something like that. And how sad, the number of years he spent cut off from this sight, and all the other beautiful things that make him feel big, and the world gentle and full of possibilities.

Johnson gets it. He tells Vasquez: You never want to go back, but you always want to remember where you came from. Remember where God brought you from. As they drive together through Oakland, past the homeless encampments, the addicts, the schoolyards, the boarded-up buildings, the new high-rises, along the freeway past the box stores and the clanking sailboats in the Oakland estuary, Johnson reminds him: Don’t forget where you’ve been.

Still, it feels good to have a home, food to eat, forward momentum, people you can count on, and people who can count on you. So few people in Vasquez’s position have all of this so soon after prison—if they ever get it at all.

Attribution: This article originally appeared in The Atlantic on December 16, 2019.