In our Behind the Scenes series, CNN correspondents and producers share their experiences in covering news and analyze the stories behind the events. CNN’s Soledad O’Brien and Stan Wilson visited San Quentin for “CNN Presents: Black in America” which premiered July 23 and 24, at 9 p.m. ET.

SAN QUENTIN, California (CNN) — San Quentin Prison sits like a fortress along the bay just north of San Francisco. It is bordered by some of the most expensive residential real estate in the country. But at the edge of this scenic peninsula, 5,400 inmates are locked up.

San Quentin has California’s only death chamber, with 656 inmates waiting to be executed.

On death row, each prisoner is confined to a cell just large enough for a bed and toilet.

Walking along these multitiered cells, where each inmate is closely monitored or escorted in shackles, reminded me of all the pain and grief endured by relatives and friends of victims like Laci Peterson, Polly Klaas or Christine Orciuch, a mother of three who was shot to death by gang member Marcus Adams in front of her 10-year-old son during a bank robbery in Santa Barbara.

Less than a few hundred yards from death row, the climate is vastly different.

We found makeshift classroom bungalows and an exercise yard where inmate Larry Faison was performing the tunes of Miles Davis with his vintage trumpet. This environment looked and felt more like a community college setting.

This is where low- and midlevel convicts are able to get out once a day. There is a tennis court, a punching bag, a baseball stadium donated by the San Francisco Giants, a library and visiting instructors from prestigious universities.

Lt. Sam Robinson, a 27-year veteran of San Quentin, gave a tour of 27 vocational programs run by about 3,000 volunteers as part of the Prison University Project, a nonprofit education program that offers many black men an opportunity to earn an associate of arts degree. It helps give those eligible for parole the intellectual tools to compete in a vastly changing job market. ![]() Inmate: It took coming to prison to see someone in school »

Inmate: It took coming to prison to see someone in school »

Advocates say that many black men imprisoned across America, particularly nonviolent drug-related offenders, have enormous potential to become productive, law-abiding members of society through higher education in prison.

University of California at Berkeley professor Rebecca Carter volunteers as a biology instructor at San Quentin. During her first semester, she was startled by what she discovered.

“I’ve been teaching on the Cal campus and teaching at the prison at the same time, and they were significantly more engaged when I was in the prison,” Carter told CNN’s Soledad O’Brien. “Not always more in command with the subject matter but more engaged, doing the homework, asking questions because they were passionate about learning.” ![]() Tour San Quentin’s Prison University Project »

Tour San Quentin’s Prison University Project »

Carter said there are also benefits for those serving a life sentence.

“There is a person in my biology class, who I know is a lifer, who has a teenage son. He was talking to me about how he was so glad to be in class because he was taking the same class that his kid was taking in high school and he could actually talk with his son about an intellectual thing, showing him that he took education seriously,” Carter said.

“He expects his children to take education seriously, and he does not want them to go down the path he went on, and he’s doing what he can to do something better for himself. And now, they could talk about mitochondria, and they can talk about ‘How did your class go?’ ” she said.

There is also the story of Willie Earl Green, whom I met in February during our documentary filming of inmates Chris Schurn, Marvin Andrews and Aly Tamboura.

Andrews, Schurn and Tamboura are all pursuing their associate of arts degrees through the Prison University Project.

Andrews and Schurn both earned their GED certificates at San Quentin. Andrews is serving a 15-year sentence for voluntary manslaughter, and Schurn is serving four years for cocaine possession. Tamboura, who tutors inmates, is serving 14 years for using a firearm in the commission of a criminal threat.

Green was serving 33 years to life for the murder, robbery and burglary of a Los Angeles woman in 1983 but always proclaimed his innocence. He earned a liberal arts degree in prison and tutored hundreds of others.

Green’s conviction was on appeal when we met, so I took a few notes but concluded that there was little chance his case would be overturned.

About one month later, I was surprised to learn that his case was indeed thrown out. A Los Angeles judge set the graying 56-year-old free, ruling that the prosecution’s star witness, Willie Finley, lied to a jury during key portions of his testimony.

“I was once a freedom marcher in Mississippi fighting for civil rights and social justice during the Martin Luther King Jr. era,” Green told me during his final days in prison. “I would never ponder harming anyone, let alone kill a human being, after spending my early life fighting for nonviolent social change the way King taught us.”

Our cameras were present at his release hearing, and we captured Green’s reunion with his wife, Mary, a breast cancer survivor.

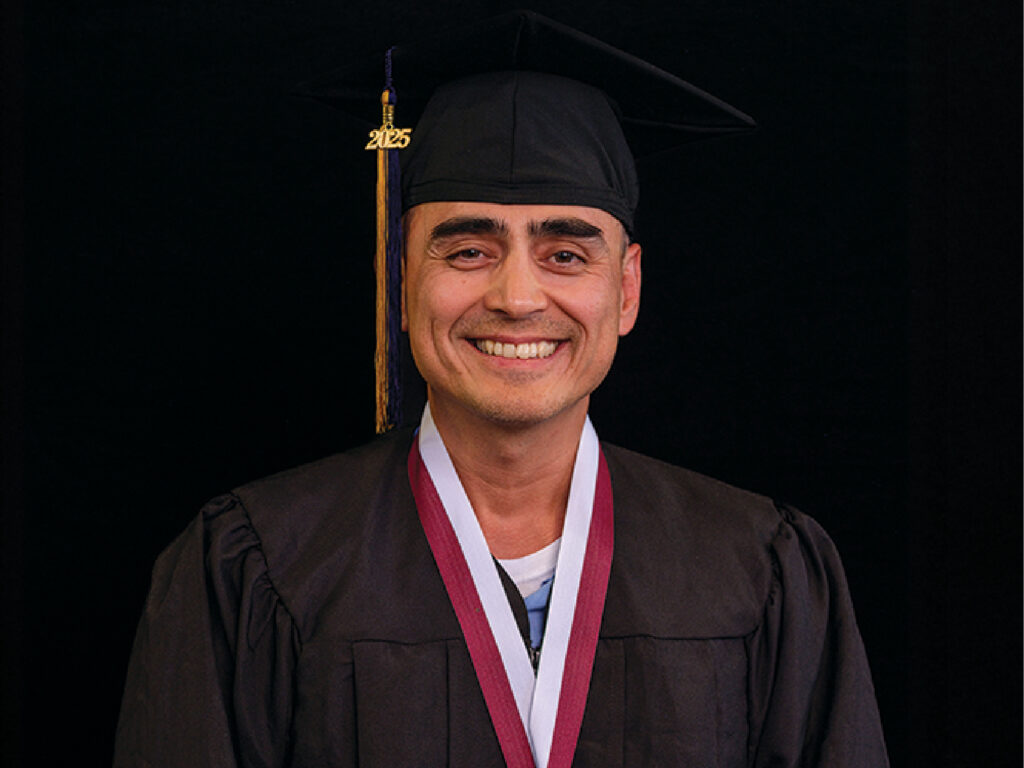

On June 19, Green was invited back to San Quentin to deliver the commencement speech for the graduating class of 2008. He received a three-minute standing ovation from more than 300 inmates, prison officials and relatives. Green was a tutor of this year’s valedictorian and emphasized the value of education.

“I learned never give up, never give up hope, and never allow anyone to define you,” Green told the audience. He told me he felt guilty about leaving his friends behind, but the experience was much different. “This time, the sound of the prison gates closing was a good ‘cling,’ ” he said.

Ninety days after his release, Green told me that he is slowly adjusting to life and that he’s not bitter.

“I don’t hate anybody,” he said. “I don’t hate Willie Finley for doing what he did. I forgive him, too.”

Although most inmates are well aware that an associate of arts degree is not a ticket to success, it’s not the end of the educational road for many ex-cons.

Several inmates have been accepted at universities, and Carter, the Berkeley professor, is convinced that higher education in prison can reduce recidivism.

“I have followed the few people who have gotten out, who got their AA here and are now in school outside in San Francisco State in Santa Cruz and actively pursuing a degree because they know that’s the way to reestablish their level of responsibility,” Carter said.

Jody Lewen, executive director of the Prison University Project, is trying to broaden Carter’s objective.

“We have to talk about how much we hate and fear them first and challenge those thinking patterns,” Lewen said. “Higher education is an opportunity to reverse the trends because demonizing black men has been good for business. I want to change that.”

But the odds against breaking the cycle of incarceration are tough. There are nearly 1 million black men behind bars nationwide, and at least 50 percent of all ex-cons wind up back in prison in the state of California for nonviolent offenses.

Attribution: This originally appeared on CNN on February 26, 2009. Read Story

Please note that the Prison University Project became Mount Tamalpais College in September 2020.