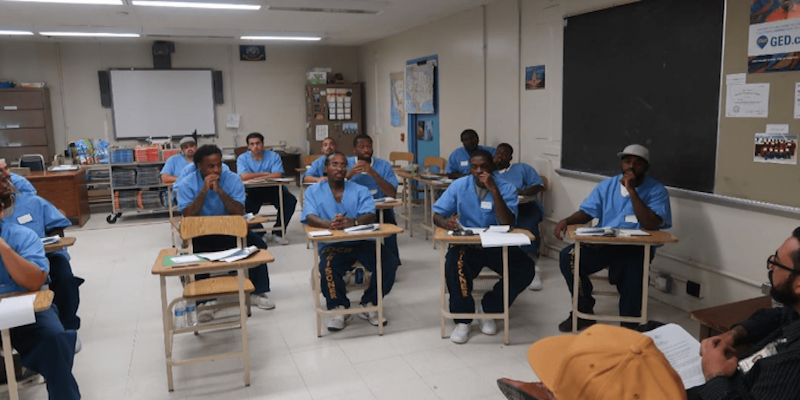

Prison University Project student and Program Clerk James King examines the dilemma of a 20-year-old incarcerated man he calls Naz.

I first met Nazhee Flowers when I was working as a teaching assistant for a college prep English class. Naz was twenty at the time and showed many of the contradictions you might expect from a young man trying to better himself but struggling to get out of his own way.

He was smart, often coming to class, listening to the discussion taking place, and making insightful comments in spite of the fact that he hadn’t read the materials we were discussing, or done any of the homework. As teachers, we struggled to find ways to engage him intellectually and resist the everyday temptations a young man in prison faces.

It isn’t hard for me to imagine him, under different circumstances, walking a college campus, perhaps going to class hung over, regretting the videos he’d posted the night before on Snapchat. In fact, to this day, the only thing that separates Naz from any other young students are the conditions he faced growing up and the consequences he faces for his choices today.

He was separated from his family as an infant, and adopted by another family when he was four years old. Over the years, he struggled to come to terms with his new family and acted out more and more at home, in school, and in the neighborhood. Then at age fifteen he was arrested and convicted for carjacking and sentenced to a fifteen year sentence.

He started off at Juvenile Hall, a place we often call “gladiator school,” because of all of the fighting that goes on there among the kids. On his eighteenth birthday, he was transferred to Santa Rita County Jail, and then, eights days later, he was transferred to a state prison. His years of incarceration in a violent Juvenile Hall made him someone to look up to among his young peers. But like most kids his age, Naz struggles to live up to their expectations.

Often, I would see him walking across the yard, just prior to class beginning, in a group of youngsters. As the semester progressed, it would take him longer and longer to peel away and come to class. Sometimes he would make appointments with me for individual tutoring, only to fail to show up. Later, I would see him on the yard with one of his partners.

The first time Naz did show up for a tutoring session, he didn’t bring his books or any of his homework with him. Instead, he shared with me something he’d recently wrote about his childhood. At age twenty, Naz was looking back over his life in much the same way I would, at a much later time in my own life. He was still striving to understand himself, minus the luxury of being able to learn from his decisions without it affecting his freedom or personal safety.

Like most people under the age of twenty-five, Naz has issues with impulse control and overcoming peer pressure. If he were free, and walking a college campus, his infractions would be understood as the indiscretions of a young man learning to make the connections necessary between our actions and consequences. On campus it may be bar fights or poorly thought out social media moments. In here, it’s melees or using a cell phone. One institution is built upon the premise that its inhabitants are there to learn. The other institution has been trained to see every independent action as a threat.

When the semester ended, I didn’t see Naz as much, but I did notice that he continued to make positive changes in his life. I saw that he joined a self-help group called Kid C.A.T., which is for people who were incarcerated at a young age, and helps them process their childhood trauma. Soon after, he started hanging around his old friends less, and spending time with guys in his self-help group more.

He also started participating in the San Quentin tours. At these tours, people from various outside communities would come in to learn more about incarceration and the criminal justice system. Naz would tell his story and answer their questions.

About a week ago, Naz came to me to tell me he was being transferred to a higher security prison. He’d been deemed a “program failure” by prison officials here because he’d received five disciplinary write-ups since coming to prison.

Most of Naz’s actions can be traced back to his age. For his part, Naz is not sad to be transferring and has come to terms with moving to a higher security prison. After all, it isn’t the first time he’s been on one of the more violent yards, and perhaps a small part of him believes the more structured environment will help him with his decision making.

His choices are really only problematic because of where he’s making them. One of his most recent write-ups was for possession of a cell phone. Phones are now common in prison, and the pathway to the outside world that they represent proves too much for most people in here to resist. Naz found his younger brother with that cell phone, someone he’d never met before. In fact, he’d also located his birth mother while in Juvenile Hall when he noticed a kid there who had the same last name as his mother. For Naz, those moments are the highlights of his young life. As he strives to discover what type of man he will be, it’s showing the initiative to find his family, being a big brother to his younger siblings, and being respected by his peers because of his experience that shows him his own potential.

My hope for Naz is that he finds a strong support network waiting for him at the next prison. I hope he doesn’t internalize a belief that he is somehow flawed, or different from other kids his age.

Still, Naz is exceptional. While here, he’s seen glimpses of his potential, and knows that he doesn’t necessarily have to conform to his circumstances, but can instead rise above them. The same kid who can find his mom, even from gladiator school, can also find the pathway to being his best self. As time goes by, he’ll gain greater control of his impulse control, and grow better at resisting peer pressure. I’m betting that, in his case, it’ll be sooner rather than later.

Please note that the Prison University Project became Mount Tamalpais College in September 2020.