My first lesson in racial discrimination happened at the maximum-security prison at Calipatria, Calif. An older Mexican dude with the signature handlebar mustache told me in a Hollywood whisper, “Hey, homie, we don’t associate with llantas (tires) around here. The animales (animals) have their own rules. We follow ours. Don’t talk to them too much because someone might feel disrespected, and you’re going to get dealt with.”

Until then, I had thought “homie” meant “homey,” as in cozy and welcoming. Here, though, the word was used to separate me from anyone who was not Mexican. The older “homie” mumbled a list of Mexican rule violations I’d get beat up or stabbed for, most involving interactions with the black guys: The phone on their side of the day room and their concrete tables on the yard were off limits. No eating, lingering or trading with them. And definitely no arguing: If a black guy so much as raised his voice, I was supposed to punch him in the mouth even if it started a riot.

I was 18 years old and scared. With multiple life sentences to serve, I knew I would have to adjust to my life behind bars. I kept to the designated areas. I spoke Spanish most of the time, and I interacted only with people who looked like me.

I did not think of myself as a racist. I had grown up playing with black, Asian and white kids in Southern California. I had attended Asian celebrations, like the Tet Festival in Garden Grove. I had eaten my black friend’s mama’s famous Cajun-fried chicken and stuffed baked potato. I thought I could teeter on the edge of the lines of self-segregation without the racist prison culture poisoning me. But I had to conform to survive.

On the yard, I stood guard at concrete benches next to toilets that reeked of urine, out of “an obligation” to hold what we had designated as our ground. I would sit around a light pole in our area that cast the only shade on the yard because it was prime real estate, at least by prison standards. The racist language of the older Mexicans who had fought in the prison’s gang and race wars became my own. I repeated the stories they told me. After a while, I grew angry and resentful myself. I lost a part of myself because I started believing the rhetoric.

I thought every California prison was segregated. But when I transferred to San Quentin State Prison in November 2016, after 15 years inside, I was appalled to see groups of black, white and Mexican inmates mingling together. The interracial baseball, basketball and soccer league horrified me. Either I was narrow-minded or these dudes were tripping.

At first, I avoided crowds. I walked alone around the yard because I did not know who to trust. I felt out of place whenever I saw people of different races just standing around together joking and laughing. I was uncomfortable with everyone else’s comfort. My old world had been simpler to navigate. Its boundaries had been clear, and I knew how to behave and communicate within them.

Then I began trying to conform to this new norm, at least outwardly. I ran in the San Quentin marathon alongside men of other races. Training was the perfect activity: It let me go along with a group while still telling myself, and others, I was participating alone. When I was running, I could not be accused of depending on anyone else.

Internally, I still struggled. My prejudices were tangled up in my sense of personal comfort, safety, complacency and custom. One evening when I got back from the yard, a black neighbor in my cellblock offered me a burrito. I was hungry, but I automatically declined. He noticed I had hesitated, looking both ways on our tier to see whether there were any other Mexicans around. He said: “Hey, brother, those days are over. This place is different. The people change you.”

My prejudice had been exposed. I felt bare. I felt ashamed I had been unable to see past this man’s skin color, unable to see his kindness and generosity because I had slid too far down the slippery slope of compromise. I wanted people to see me for more than the crime I had committed, and yet I was unable to see beyond skin tone.

I started venturing out of my comfort zone because I wanted to change. I would stop people on the yard to talk about their day. I started befriending guys of different races who were fellow members of a self-help group — men who were also working to heal their family relationships and make amends for their crimes. Our pasts were similar, full of pain, regret and remorse.

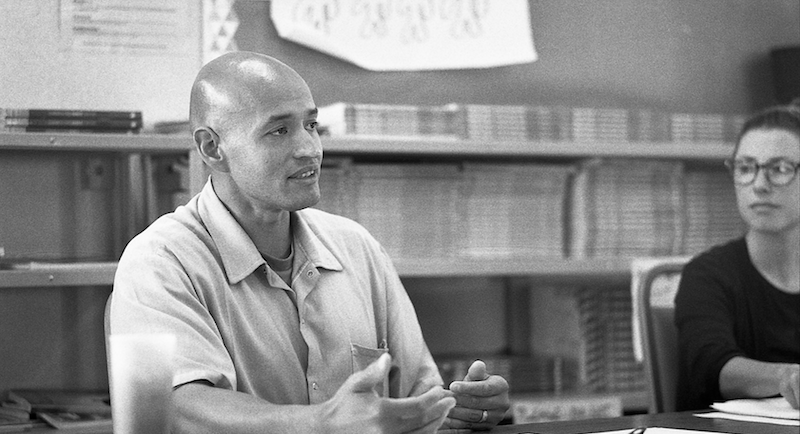

As part of these efforts, I joined the San Quentin News, our prison newspaper. The teacher of the weekly journalism class said reporting makes a difference because it informs people about the world and the options out there. For a long time, I did not know there was any reality other than the one I knew. I wanted to help share how the world is much bigger and brighter than what we sometimes see.

When I first started working in the newsroom, the editor in chief, a lanky black man named Bonaru, told me, “See where you fit in, and we’ll help you along the way.” One day, I almost lost it when he scolded me for sneaking a peek at my story on the managing editor’s computer. I was not used to black people telling me what to do. But I checked myself, and he explained the chain of accountability.

Beyond that lesson in interracial work relations, though, he believed in me. After so much time in prison, with few challenging opportunities, I had a serious confidence problem. Bonaru pushed me to learn the computer program I was nervous to use, saying, “Unless you try it, you won’t learn. And if you make mistakes, I’m right here to fix them.” I eventually learned how to lay out a newspaper and Photoshop images. Bonaru taught me that the undo command, ‘Control-Z,’ works in my favor, and he helped me realize there are other things in my life I can fix, too. We still work together today, on neighboring computers. He is one of my best friends and mentors.

Although there are people in San Quentin stuck in a mentality of “us against them,” I have a wide circle of friends of other races, men I confide in and consider my brothers. These friendships have awakened dormant feelings of compassion, sadness and longing. I have come to understand why it was hard for me to see I could live like this and there was an alternative way to think. I see pop culture and even news on television — the few windows I have into the outside world — constantly reinforce racial stereotypes. I see the inequity that fuels racial tensions elsewhere in America. I see how people on the outside are also shaped by their environments. Their behaviors become their beliefs, and vice versa. Despite my fears for my self-preservation, I confronted my biases and worked to change my perspective. Maybe society can do the same.