Former Prison University Project instructor Nigel Poor collaborated with many of our students to put together an exhibition at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Archive.

It started with a box of negatives.

In 2012, Bay Area photographer, educator and podcast host Nigel Poor was one year into teaching the course “Visual Concerns in Photography” at San Quentin State Prison when administrators gave her a box containing thousands of unorganized negatives—images produced between the 1930s and 1980s—from the prison’s archive.

Out of this material chaos, Poor and her students gained a profound understanding of photography as a tool for personal development, and learned how it both serves and undermines rigid institutional narratives. The San Quentin Project: Nigel Poor and the Men of San Quentin State Prison, on view at Berkeley Art Museum Pacific Film Archive through Nov. 17, shares the fruit of that knowledge with the public.

Poor volunteers at San Quentin through the Prison University Project, a nonprofit organization that offers higher education opportunities to incarcerated men. The class she teaches works with students to develop visual analysis skills, a goal achieved through assignments she calls “mapping exercises.”

Poor’s use of the word “mapping” to describe this work is a minor yet compelling detail. Maps represent knowledge; they make it clear who produces and controls the information within them, and for whom that information is intended. The opportunity to work with images created within the prison industrial complex, but without the supervision of that authority, meant that Poor’s students could freely interrogate the official narratives the images convey.

In one assignment, students deconstructed a range of photographs made by notable photographers such as Joel Sternfeld, analyzing what they saw “like a crime scene to be studied, written on, and mapped to reveal its undisclosed story,” Poor relates in a gallery text panel. On the back of each double-sided image, students composed personal responses to the scenes. Six of these minimally framed objects hang in a circle at the center of the BAMPFA exhibition. Reading them is to witness basic visual analysis transform into absorbing and unexpected narrative arcs that begin and end on the same page.

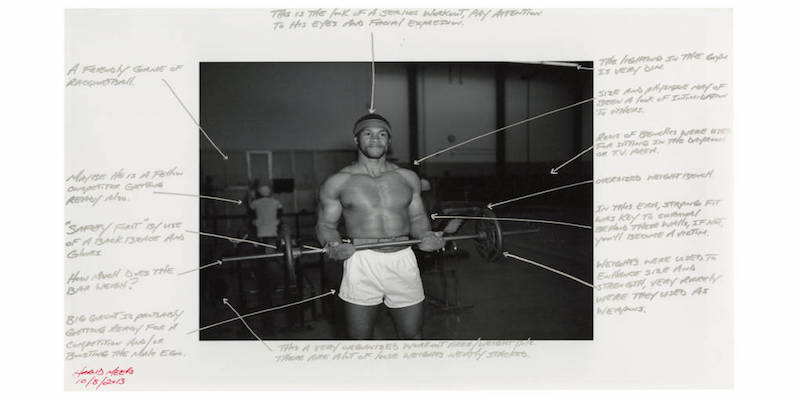

Students next applied their burgeoning analytical skills to images produced from Poor’s prison archive cache. After printing the photographs and organizing them into rough categories, Poor again asked her class to write down what they saw. As visitors see in framed images hung on one of the gallery’s long walls, scrupulous notes attest that no detail was insignificant. Unlike earlier mapping exercises, Poor’s students were now examining images captured on their turf.

The students saw familiar spaces—inmate cells, administrative offices and public areas—being used by the men who came before them. The scenes can be blissfully ordinary or sobering: a father seated on the grass with his baby, a cell tossed for contraband items.

On the opposite gallery wall, The San Quentin Project presents many of the same images unembellished, without commentary. A telling juxtaposition—starkly visualized by an image of a CO (correctional officer) holding up a knife confiscated after a stabbing—implicates photography as it supports specific, authoritative narratives. In one image, block text at the bottom reads simply “stabbing in gym.”

In the companion image, Shadeed Wallace-Stepter notes the officer’s inscrutable expression, writing, “Doesn’t look like he’s been affected by the incident at all. Makes me wonder if he’s always been like this or if the job is responsible.” Wallace-Stepter recognizes the officer’s humanity, his relatability, in an institutional system that has a tendency to dehumanize all caught within it.

The San Quentin Project: Nigel Poor and the Men of San Quentin was produced by Poor and former SFMOMA curator Lisa J. Sutcliffe for the Milwaukee Museum of Art. Since its lauded debut in late 2018, conversations about the links between slavery and mass incarceration and pushes for prison sentencing reform have helped shape a difficult and long-overdue critical dialogue. By hosting this important project a mere 14.5 miles from San Quentin State Prison, BAMPFA brings those ideas—through images—home, making them all the more immediate for Bay Area residents.

Please note that the Prison University Project became Mount Tamalpais College in September 2020.