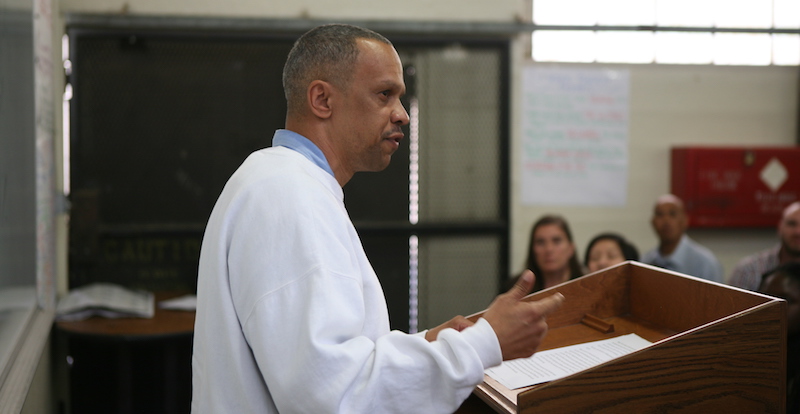

Prison University Project student and Program Clerk James King writes on voting, art, and rehabilitation.

Right now there is a lot of debate about whether incarcerated people should be given the right to vote. It reminds me of a similar dispute about the value of art in educational spaces. Many of the proponents for voting rights argue that allowing incarcerated people to vote will create better citizens, much in the same way that art advocates argue that a well-rounded education (read: one that values art) will create more well-rounded citizens.

There is a link between art and voting that is fairly obvious. Both are means of expression, and therefore deeply personal. But before exploring the similarities between the two, one fact must be established first.

Art does not rehabilitate.

Art is the result of one’s experiences or perceptions expressed creatively. As such, let’s say a person’s art springs from their unresolved trauma. Said art, like all trauma, may be expressed either harmfully or healthily, but it doesn’t become rehabilitative simply because it’s expressed. That is true, even if it feels good to express oneself. The fact that art, and the response that art generates, is affirming does not necessarily make it rehabilitative.

Sure, there is a basic intrinsic value to self-expression, but what if that expression is ignored, misunderstood, or worse, rejected by one’s peers? In situations like that, the responses to expression itself can further the trauma. Art didn’t save Mozart, Janis Joplin, Tupac, or Jimi Hendrix, any more than it saved Charles Manson.

It’s similar with voting. Imagine, for instance, I bought my potential fiancée an engagement ring, then the night before I popped the question, someone breaks into my house and steals the ring. At this point, I might believe the death penalty is too good for this criminal. Then, a potential law is placed on the ballot. This law will give all burglars life sentences. Hell, yes, I say. Early in the morning, I march down to the voting booth and vote yes. Am I now rehabilitated? What if I vote the same way on the next ten initiatives?

The truth is that what rehabilitates is the commitment by a community to invest in those among them who are traumatized. Compassion and empathy are the bricks. Kindness is the mortar. The work of rehabilitation is painstaking, tedious, with numerous setbacks. A wall goes up, then the wind knocks some of the bricks down before the mortar fully solidifies. Since the building cannot exist without the wall, we replace the bricks one by one.

If the value of art is not in rehabilitation, then what is it? Instead, art’s value springs from something far more basic. Art is expression and expression is a fundamental need of human beings. In fact, I would argue that self-expression is just as essential to life as breathing.

In a similar vein, considering whether voting is rehabilitative misses the same larger picture. Voting is expression. The denial of the right to express one’s self creates a second-class citizen in a society that promotes the concept that we are all created equal. If people are denied their voice in one way, they will surely find another. In fact, it’s important to remember that voting takes many forms. People vote with their actions far more often than they do at the voting booth. Take legalized marijuana, for example. Long before “voters” went to the polls in California and “voted” for legalization, thousands of people were voting for it to be legal. Instead of going to the polling place, they voted with the local weed man.

Voting should be allowed, not because it’s rehabilitative, but because it’s humanizing. If that’s true, then I guess it is actually rehabilitating….for our society as a whole.

Please note that the Prison University Project became Mount Tamalpais College in September 2020.