Dear friends,

I hope everyone is doing OK, during this extraordinarily complex and painful time.

I’ve been struggling to write this latest update for the last several weeks, and it is not getting any easier. Last week San Quentin reported its first confirmed cases of COVID-19, apparently the result of transferring people from the California Institution for Men, in an attempt to shield them from the massive outbreak there. For statistical details of the current situation across the state, see the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation’s website, which now lists numbers of cases, people tested, and deaths.

What the numbers of course cannot convey is the terror of this situation for people inside and those who love them. Watching the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases climb while it gradually spreads to more prisons is like watching a fire jump from one building to the next, with tens of thousands of people trapped inside. A handful of passersby see what’s happening; some stand and watch; most just walk by.

Right now, hundreds of thousands of incarcerated people are confronting the threat of COVID-19 in squalid, medically unsafe prison cells and dormitories; with inadequate nutritious food, personal protective equipment, hygiene articles, educational materials, accurate scientific information about the virus, or current news. Their ability to communicate with loved ones, about whose physical health or economic situation they may be deeply worried, is severely limited. They are also justifiably terrified. Some, especially those who are already in ill health or elderly, are expecting to die.

Yet in spite of the formidable advocacy work being done for the release of the medically vulnerable and/or elderly, scant resources are being invested in even the most basic needs of those who remain inside. In the midst of the current explosion of awareness, outrage and solidarity, when literally the entire world’s attention is focused specifically on racist state violence and neglect, the normalized brutality and negligence of conditions inside the U.S. prison system remain of little interest to most Americans.

It’s not hard to understand why people seeking to address the crisis of COVID-19 in prisons would focus on trying to remove people from that danger. Yet most of us would agree that even the most herculean efforts are unlikely to bring about the release of more than 10% of the population. It would thus seem (to put it mildly) logical to also invest resources in the most immediate health and safety needs of both prisoners and staff. Yet most of the largest criminal justice advocacy and philanthropy organizations remain almost entirely focused on the cause of releases, rather than also addressing conditions inside.

The most pressing issues right now relate specifically to supplies, facilities management, and operational policy: Procuring adequate personal protective equipment, cleaning supplies, healthy food and water; repairing or replacing ventilation systems; overhauling the prison TV systems; installing adequate IT infrastructure to support technology-based delivery of education, visiting, medical care, psychological services, and recreational activities; revising Departmental policy regarding allowable materials and access to technology; navigating legally complex labor/management issues (e.g., screening and testing, forming staff cohorts to limit virus spread); and making emergency funding rapidly available for all of these things, as well as for washing machines, changing facilities, quality food services, hotel rooms and other facilities, to support staff mental and physical health. The Department also needs to have emergency plans in place, in the event that staffing shortages become more acute; large numbers of prisoners become severely ill when local ICUs are already overloaded; fire season further degrades the quality of air in the housing units; or an earthquake isolates the institution for an extended period of time.

Tackling these types of projects requires deep familiarity with Departmental policies, as well as close collaboration with staff and administrators. Unfortunately, those communities and organizations that are typically most concerned about the wellbeing of incarcerated people are generally those least likely to be connected to the relevant professional networks. They are also the ones that people working in corrections are most likely to feel threatened by. Those organizations that do have strong contacts inside the world of corrections are often reluctant to openly address issues like living conditions. Other advocates are averse, either as a matter of principle or of public image, to the idea of engaging in a practical sense with prisons. Those who control the prisons and those who care about the people inside are traditionally conditioned to view each other as enemies.

One wonders what would happen if the world of corrections were not so isolated and distrustful of “outsiders,” and if it were subject to vastly more external oversight and accountability. Yet the refusal of large segments of the advocacy community to engage directly with incarcerated people—to, in a sense, look them in the eye, to recognize them as more than a remote, unfortunate abstraction—is a long-standing problem. And its already dire consequences are now escalating sharply.

But this failure to fully register currently incarcerated people as living human beings is not just a moral issue; it is also strategic. Incarcerated people are not only passive subjects of the system; they are also potentially extraordinary agents of change. This country’s greatest experts on systemic racism, as well as on police, prosecutorial, and judicial abuse, live in its prisons, and they are unparalleled advocates and witnesses. Tending to their wellbeing while also amplifying their voices—not just after they have survived incarceration—is an essential strategy for bringing about large-scale change.

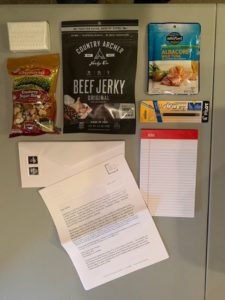

At the end of April, the Prison University Project created two initiatives. The first was to distribute gift bags to all of the nearly 3,900 people incarcerated at San Quentin. Each one was packed in a gallon-sized Ziploc bag, filled with beef jerky, tuna fish, trail mix, a bar of soap, a small pad of paper, envelopes, stamps, pens (or pen fillers, for those in housing units where regular pens are not allowed), and three articles: Why Soap Works, by Ferris Jabr; The Pandemic is a Portal, by Arundhati Roy; and Five months on, what scientists now know about the Coronavirus; by Robin McKie. We also included a letter that explained the package.

The response from inside was unexpected and profound. Within days, we began receiving hundreds of thank-you letters. Some were from our students (who comprise about 10% of the overall San Quentin population); others came from the vast communities in Reception and on Death Row. With permission, we are sharing a small sample of those letters here. We intend to post more in the near future.

While everyone expressed appreciation for the package’s contents, the thing they stressed the most was the impact of the message it conveyed: There are people on the outside who are thinking of you, and who care. A lot of people described the actual emotional sensations of receiving it—and of realizing it was a gift for them; the way it changed the atmosphere of the whole housing unit, the sounds of joy on the tier. Some described how it transformed their mood, or even their sense of themselves as human. Others said it inspired them to be kind; gave them hope about the future; or strengthened their resolve to keep going. A handful shared artwork or poetry. Many had been in prison for decades. Some had not received mail or a package in years; a few never had. The enclosed articles contained the first information many had ever received on the science of COVID-19. Quite a number expressed gratitude on behalf of others in their unit, reminding us that some people we would not hear from because they cannot read or write.

Some people shared their fears about getting sick—especially those with serious medical conditions, or who are older. Many more expressed concerns about loved ones on the outside, and the frustration of not being able to be there for them. Others described their bleak living conditions—poor ventilation, barely any time outside, scarce cleaning supplies. Many requested reading materials, puzzles, legal information, or a pen pal. A significant number of people acknowledged CDCR’s efforts to prevent the spread of the virus, but also described the impossibility of social distancing, particularly in dorms or showers, and their fear and frustration about some staff’s inconsistent use of masks. People in Reception shared their extraordinary frustration with being stuck indefinitely in a housing unit with no TVs or radios, since COVID-19 had caused transfers to be indefinitely suspended.

Together, the letters provide remarkable testimony about what it is like to be in prison, especially right now—and not just materially, but psychologically. Most of the “public speaking” and outreach I’ve done since the letters began arriving has entailed my channeling what I’ve learned from them to the outside world. This is more or less a continuation of what my job has been like for the last twenty years, but now with some much higher stakes.

The other for-us unprecedented initiative we undertook in April, also with funding from an individual donor, and tremendous support from the San Quentin administration, was a food truck appreciation event for prison staff. Over the course of a single day, from five in the morning till eleven at night, several Mexican food trucks served burritos during each of the three shift changes to well over a thousand people.

At San Quentin, nearly half of all employees are medical workers and other non-custody staff. The rest are custody and administrators who work throughout the prison. Those on site right now are those who cannot work from home. Most come in sustained direct contact with other people there, and thus experience some level of at least potential exposure to COVID-19.

Over the course of the day, the long, wide stretch of pavement that overlooks the Bay on the way to the Count Gate was transformed into something faintly like a street fair. Second watch staff started arriving in the morning, when it was still dark; a steady stream heading towards the gate, lugging gear or water, some chatting, some with heads down. Throughout the day faces puzzled and then eventually brightened with a smile once they finally believed that the food really was there for them.

Most people who work at San Quentin commute long hours each way, often with van pools. Hundreds also live in trailers on or near prison grounds because there is virtually no affordable local housing. Most prison workers feel some degree of dread or danger about being at work; the pandemic is obviously compounding the physical and mental toll of the job beyond measure. At a time like this, it felt meaningful to be able to offer something so simple and positive. I wonder how the climate of the prison might change if staff—and everyone else—felt that taken care of every day.

As of this writing, we are working to arrange a similar pair of initiatives, this time at a prison in the Central Valley with over 4,000 incarcerated people, 1,000 staff, and a serious COVID-19 outbreak. Depending on our fundraising capacity, and the receptivity of other institutions, we hope to continue these efforts even further in the future.

For several weeks I hesitated to write about these projects, loath to turn bleak lessons about long-term exposure to extreme emotional and material deprivation and toxic stress into a feel-good story about us. But the intensely positive emotional responses to these initiatives illustrate vividly both the need and the opportunities that I urgently hope to convey. Both events also permanently altered my understanding of what it means for any act of goodwill to be effective, significant, or trivial, in a way that I hope will inspire others to do something, anything, rather than just standing by. They also strengthened my resolve to continue doing whatever we possibly can to provide material and emotional support to the entire community at San Quentin, as well as other institutions.

So we will continue… working to ensure that all incarcerated people and prison staff have plentiful access to personal protective equipment and supplies; facilitate the flow of information to the outside world about institutional conditions, needs, challenges, and solutions; foster productive dialogue and collaboration between diverse individuals and organizations; educate and advise journalists, policymakers, family members and other stakeholders; provide quality reading materials and other paper and video-based supplies for education, recreation, and health; support the research and program development efforts of funders; and organize resources in support of people who are now leaving prison during the pandemic.

Above all, we will do everything in our power to make heard the voices, and the vision, of our students and all the other people throughout the system, to mitigate as much as possible the harm of COVID-19, and to help the world understand that they are human beings whose lives have value.

Jody Lewen

Executive Director

Please note that the Prison University Project became Mount Tamalpais College in September 2020.