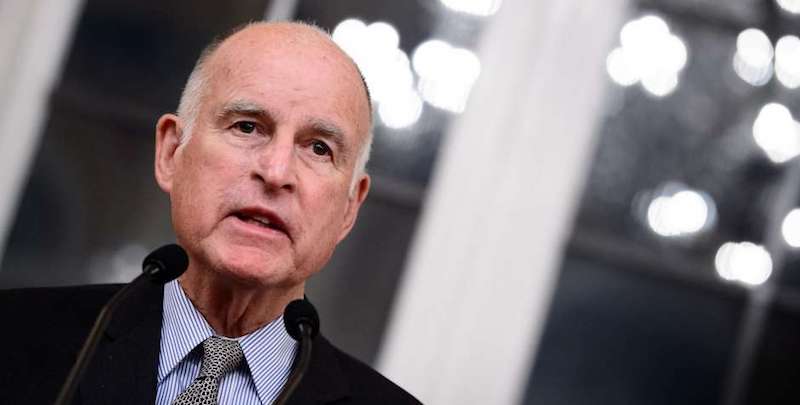

Gov. Jerry Brown commuted my sentence in December from 67 years to life to 20 years to life — a rare act of mercy. I had imagined the effects of a commutation on my life; the commutation’s effect on incarcerated people at San Quentin State Prison, though, surprised me. The night of my commutation, men cheered in their cells like the 49ers had just won the Super Bowl. It felt fantastic to hear men call out to me with joy, but I also recognized that they weren’t cheering for me. They were applauding something much more important than me.

That “something” is difficult to convey, as it showed up in emotions more than in concrete events. In their questions, I heard a thousand times: Emile, why do you take so many self-help classes? Why are you always reading? Who are you trying to impress? These questions didn’t come from everyone; but when they came, they felt loaded with judgment.

I felt like people wanted to tear me down.

I was wrong, people hadn’t wanted to tear me down. Their concerns were analogous to those of Denzel Washington’s character in the film “Fences.” He degraded his son’s sports dreams in a misguided attempt to protect his son from disappointment. Listening to them cheering for my commutation, I realized that what I’d taken as judgment was fear for me. My questioners had anticipated my “inevitable disappointment” and wanted to protect me, in their imperfect way.

Now they cheered, because they’d been wrong. And they’d never been happier to be wrong.

“They don’t give that kind of stuff to people like us, you know?” one man told me. “That kind of stuff is only for other people.” He had a thunderstruck look that reminded me of my own arrival at San Quentin. I met dozens of free people (volunteers in the prison) who wanted me to succeed — which wasn’t consistent with my internal narrative about a society that wanted me to fail. I’d found a community that wanted me, and I had never admitted to myself how desperately I wanted that. It proved an epiphany in my rehabilitation.

Six years later, I witnessed a similar moment of realization by the man who thought commutations were only for white people or rich people. His narrative, common in prison, about an “entire system” arrayed against him, was cracking.

A father spoke to a room of incarcerated journalists who work on the prison newspaper and radio news program about the effects of my commutation on him. “Before Emile, I wasn’t doing anything,” he said. “I didn’t care … I was never going home. Now, I’m going to do something.”

His sentiment isn’t isolated; I’ve watched it spread from man to man all month. I’m at the middle of how Gov. Brown’s act of mercy fuels exponential change. People who said they “didn’t care” are admitting to themselves that they both want to care and can be restorative members of their communities. They’re energized to transform their lives; and their transformations can change the lives around them, just as my transformation ripples through the world around me.

Media coverage billed me as “a more obvious choice” for clemency and a model of rehabilitation. I’m humbled. And I respectfully offer that in 20 years I learned to be this man from a lot of worthy men who don’t have my writing skills and so don’t have my visibility. Hundreds of them will file for a commutation this year. Imagine the power to spread transformation in a hundred acts of mercy.