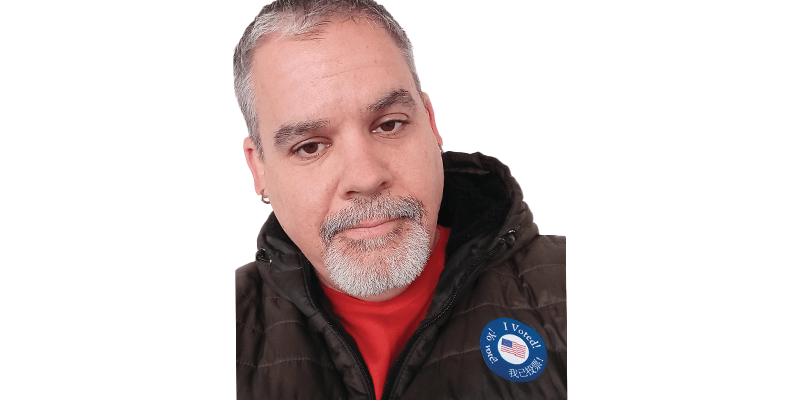

On February 15, 2019, Prison University Project students participated in the second annual Ethics Bowl competition against a team of undergraduates from UC Santa Cruz. During this non-confrontational alternative to the traditional competitive form of debate, teams discussed restoring voting rights to ex-felons and issues of animal welfare vs. religious freedom in a new Belgian law regarding the slaughter of animals. We are proud to say that the San Quentin team—comprising Randy Atkins, Angel Flores, and Roosevelt “Askari” Johnson—won for the second year in a row. They prepared their arguments and cases over the course of two semesters with the help of coaches Kathy Richards, Kyle Robertson, and Connie Krosney.

Presenting first, Prison University Project students argued that ex-felons should regain the right to vote, but only after they’ve completed their sentence and fully rehabilitated. They argued that disenfranchising ex-felons is to condemn them to a “social death,” and publicly reassert that they don’t matter and aren’t valuable. Though the students acknowledged that clear racial dynamics were in play in preventing people of color from voting, the students turned to social contract theory to argue that breaking a law means forfeiting rights. Thus, one must rehabilitate to regain that right. In their rebuttal, the UC Santa Cruz team agreed that ex-felons should regain the right to vote, but they pushed back on this question of forfeiting and regaining rights asking, “What if reform programs are not available? And what if one can’t rehabilitate?” They also raised the issue that this argument plays into the assumption that incarcerated people “are broken” or have something wrong with them that need to be fixed. Challenged by the judges as well, the Prison University Project students grappled with whether or not voting was an absolute or conditional right.

In the second round, UC Santa Cruz presented first on the question of whether or not a Belgian law banning unstunned slaughter of animals was ethical to enact though it conflicts with religious traditions of Islamic and Jewish communities (halal and kosher practices). They argued that the law was not unethical; there was no outright ban on meat, it was not based on anti-Semitic or anti-Muslim sentiment, and it was actually a more compassionate way to slaughter animals. UC Santa Cruz took a consequentialist perspective thinking of the outcomes of the law—animals are more humanely slaughtered and religious communities are still able to access meat. To them, the state’s intent was to alleviate animal suffering, not curb religious freedom. Prison University Project students argued an opposing stance, questioning if the research proves it is actually more humane to stun before slaughtering. They raised the point that halal and kosher practices were created specifically for humane slaughter, and that the modern Belgian law was clearly motivated by discriminatory sentiment. By painting Jews and Muslims as barbaric “others” for how they slaughter animals, the Belgian government was sowing further discord between religious communities. The judges engaged once again and asked UC Santa Cruz where the line is drawn between the state promoting compassion and limiting personal and religious freedom.

After a tally of votes, the judges concluded that the Prison University Project beat UC Santa Cruz by a slim margin. All participants and attendees agreed that the Ethics Bowl format was a wonderful intellectual exercise of bringing philosophy out of the academy and into everyday life and—in this case—into prison. For more information, see San Quentin News‘ coverage of the event and video footage from the 2018 Ethics Bowl.

Please note that the Prison University Project became Mount Tamalpais College in September 2020.