Attribution: This article originally appeared in SFWeekly on April 29, 2021. Read Story

When a COVID-19 outbreak ravaged San Quentin State Prison last May, infecting over half the incarcerated population and killing 28 prisoners, Juan Haines was one of the inmates who tested positive. Rather than placing him in the already maxed-out infirmary, guards moved him to Badger Unit, one of the prison’s solitary confinement wards.

He was quarantined in cell 314, a squalid 4-foot by 10-foot enclosure with no electricity. He was provided scant medical attention and let out only to shower once every three days. Perched on the top bunk, Haines turned to writing. Using pen and paper, he documented the harrowing conditions of the prison and sealed his report in an envelope.

He addressed his letter to the editors of The Appeal, a news outlet dedicated to telling the stories of underserved communities, including the experiences of incarcerated individuals. San Quentin’s treatment of sick inmates was no longer a secret.

“People were dying left and right,” Haines said during a collect-call telephone interview for this story. “I’m housed in North Block. We’re pretty much double-celled in there, so it was already overcrowded. It was particularly deadly because the buildings are unventilated and the windows are welded shut.”

When Haines penned his letter, he was not only reaching out to a group of fellow human beings, he was also appealing to a professional kinship. Haines is a journalist — an incarcerated journalist — reporting from within an institution historically synonymous with silence.

As the senior editor of one of the few prisoner-run newspapers in the nation, the San Quentin News, Haines and his incarcerated colleagues work with a team of professional volunteer staff and advisors to produce a monthly paper distributed to inmates across California prisons. Known as “the pulse of San Quentin,” the San Quentin News is a vital source of information for individuals doing time throughout the state, as it provides updates on new state policies and the latest on reform efforts.

In 2015, reporters like Haines were officially recognized as professionals when they became members of the Society of Professional Journalists. Under the guidance of the SPJ, the first chapter inside a prison was born.

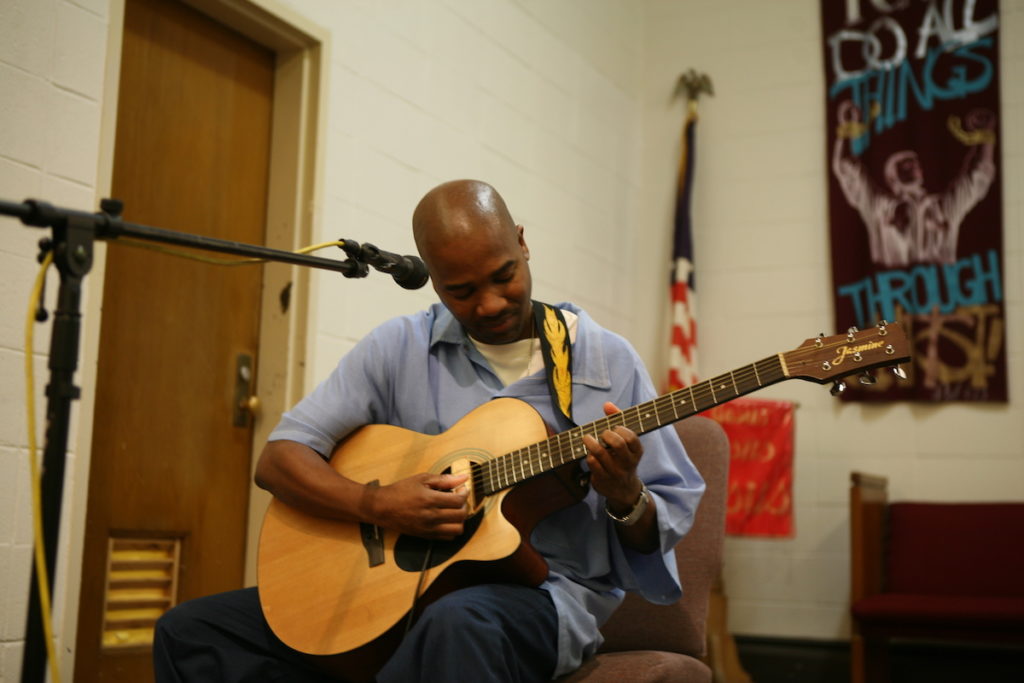

Today, over 40 incarcerated journalists work inside the walls of San Quentin, writing and producing print, radio, and video journalism that has been published locally and nationally in a variety of outlets — including The San Jose Mercury News, The Marshall Project, The Appeal and KQED.

Inside Scoop

In addition to providing his fellow inmates a stream of information tailored to their daily lives, Haines and his peers come to the table with a perspective that few, if any, reporters on the outside could hope to offer.

When COVID-19 hit, the San Quentin journalists — much like members of the press trapped inside the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6 — were faced with a potentially lethal challenge and a serious scoop. It was the exclusive nobody wanted.

The crisis erupted shortly after the transfer of inmates from the California Institute for Men, a prison already suffering through a major outbreak. The transfers, some of whom hadn’t been tested in up to four weeks, mixed into the San Quentin population.

Haines, who tested positive for COVID-19 in June, wrote a number of stories about the conditions that made San Quentin susceptible to the deadly outbreak, exposing the failures of prison administrators along the way.

Inside the walls of the crowded San Quentin — one of several California prisons operating at more than 100 percent capacity — prisoners feared reporting their symptoms, lest they be quarantined in solitary confinement. Some had the once-a-year privilege of seeing their children revoked due to the outbreak. Others lived out their final days in their cells.

The California State Senate is currently investigating the San Quentin COVID-19 outbreak. Many prisoners have filed lawsuits and petitioned to be released or relocated. Although San Quentin’s COVID-19 rates have dipped in recent months, infections across the California Department of Corrections’ 35 prisons persist among many of the system’s most vulnerable populations. Over the past year, almost 50,000 CDCR prisoners have tested positive for COVID-19; 222 have lost their lives.

“It’s terrible. It’s a human rights crime of the highest order,” says Hadar Aviram, a UC Hastings law professor. In October, Aviram wrote a case brief on behalf of the ACLU of Northern California, which was representing San Quentin prisoners. That brief ultimately led the California Court of Appeals to rule that the CDCR administration had acted with “deliberate indifference” in their handling of the outbreak. The court ordered the CDCR to reduce San Quentin’s prisoner population to 50 percent capacity.

In late December, the California Supreme Court sent the case back to the Court of Appeals, effectively putting the order on hold. Today, activists around the Bay Area continue rallying for fair treatment of those behind bars. Aviram, who many regard as a leading voice of prison reform advocacy, says the ongoing litigation around safeguarding inmates during the pandemic amplified the need for reform many have long been fighting for. “I think the virus is illuminating a lot of pockets of suffering and neglect that were there before.”

Aviram works closely with local advocacy groups. Most recently, she’s joined forces with the Stop San Quentin Outbreak Coalition. The coalition, composed of lawyers, family members of inmates, former prisoners, concerned citizens, and young activists, marched to the prison walls in July with bullhorns and banners — publicly demanding that Gov. Gavin Newsom reduce the incarcerated population and take action against the California prison outbreaks.

Aviram says the work of the incarcerated journalists has been essential to activists. “What we desperately need is people trying to advocate for people inside. We can only advocate if we know the facts,” Aviram said. “Folks like the San Quentin News are doing a crucial job because they are the ones closest to what’s actually happening. They’re the ones getting the stories. It’s crucial to have journalism behind bars.”

According to Rahsaan Thomas, an incarcerated journalist interviewed for this story, prison officials do not censor the San Quentin News unless a story incites violence or is perceived to be disruptive to prison security. “As long as there’s no security issue, they can’t tell us what to say, and they generally don’t,” Thomas says.

As for the way members of the prison population — or powerful individuals on the outside — perceive his work, that’s a different concern.

“I do feel like I have to be careful about how I word things sometimes,” Thomas continues. “It could hurt me on parole board. It could affect politicians’ decisions on letting me go early. I am mindful of that.”

Thomas, who’s serving 55 years-to-life for second-degree murder, has developed considerable influence as a chronicler of prison life.

Through the pandemic, he curated an online art exhibit called “Meet Us Quickly” centering the work of incarcerated artists with the Museum of African Diaspora. He is the co-producer and co-host of a podcast called Ear Hustle, which boasts over 20 million downloads. Working in collaboration with outside producers, Thomas shares snapshots of his daily life with the intent of breaking down stereotypes about people behind bars.

“You get entertained and you also understand we’re just like you,” Thomas says. “They see you as a non-human, of course, they’re not going to help you. It’s very important to have journalists in here to get the story right so the public gets the full picture and correct information and they can make the best decisions when it comes to breaking these cycles.”

More to Say

As the saying goes in the news business, “If it bleeds, it leads.” And the Marin County prison’s battle with COVID-19 has served to draw a new wave of readership to the San Quentin News.

But the journalists working inside the prison are interested in plenty of topics that have nothing to do with the virus, and their mission — to “report on rehabilitative efforts to increase public safety and achieve social justice” — remains a guiding force.

“I’ve been at San Quentin since 2007, and I’ve been reporting the good, the bad, and the ugly,” says Haines, who’s serving a 55 years-to-life sentence for robbing a bank in 1996.

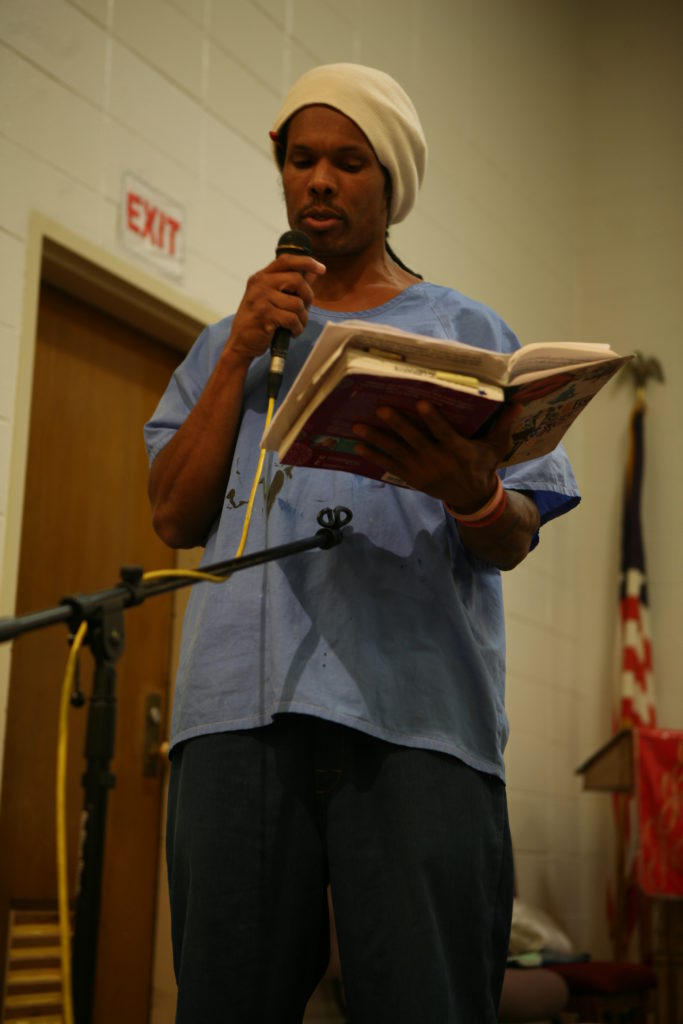

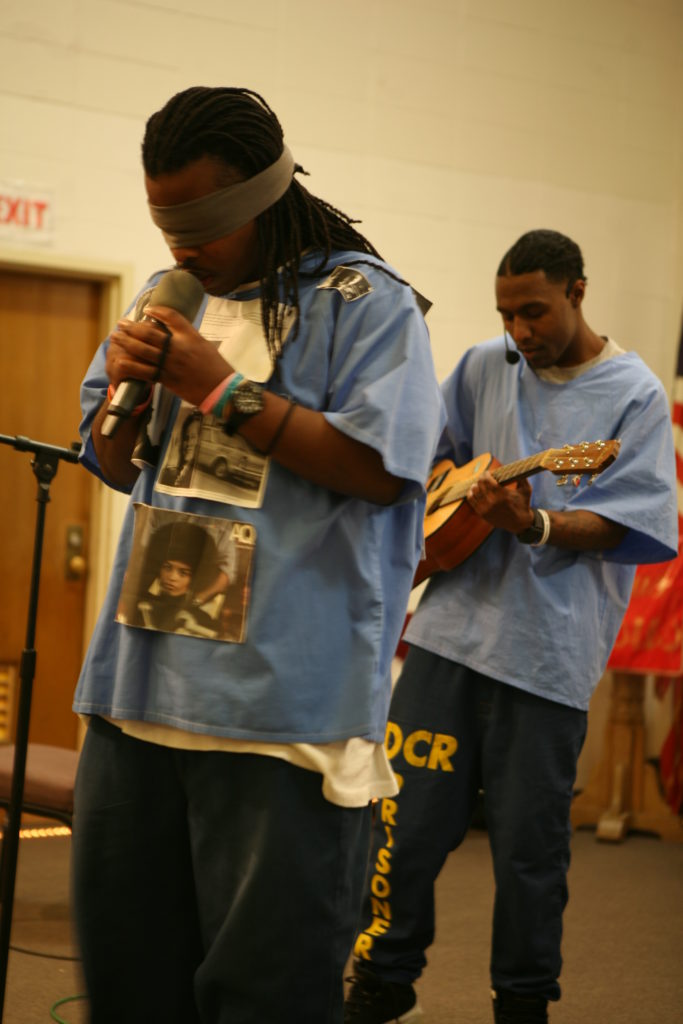

“There’s a lot of great things that happen here as far as rehabilitation is concerned, and the opportunities for people to show accountability, redemption, and rehabilitation.”

Open some of the latest editions of the paper and you’ll find hundreds of inmates in caps and gowns graduating from rehabilitative programs, op-eds about Newsom’s new reform policies, or an inmate earning his Master’s of Business and Administration degree. Other editions feature prison administrators and inmates working together to host their annual Mental Wellness Week; Google executives visiting participants of the prison’s coding class; a sit-down visit between the San Francisco Police Department and the men they put behind bars; or public defenders stopping by for a four-course meal prepared by “San Quentin Cooks,” a rehabilitative program aimed at teaching skills for reintegration into the workforce upon release.

“Incarcerated people housed in jails and prisons all over the country write into the newspaper seeking to receive their own copies of the newspaper. Issues that are relevant in California are also relevant elsewhere,” says Lt. Sam Robinson, San Quentin’s Public Information Officer and administrative supervisor of the San Quentin News. “The stories I see that resonate the most are the success stories of people graduating with high school diplomas, GEDs, vocational certificates, or college degrees in addition to the stories of how people have grown and changed their lives through participation in rehabilitative programming, inspire others that they can evolve and have life-changing accomplishments as well.”

Success Story

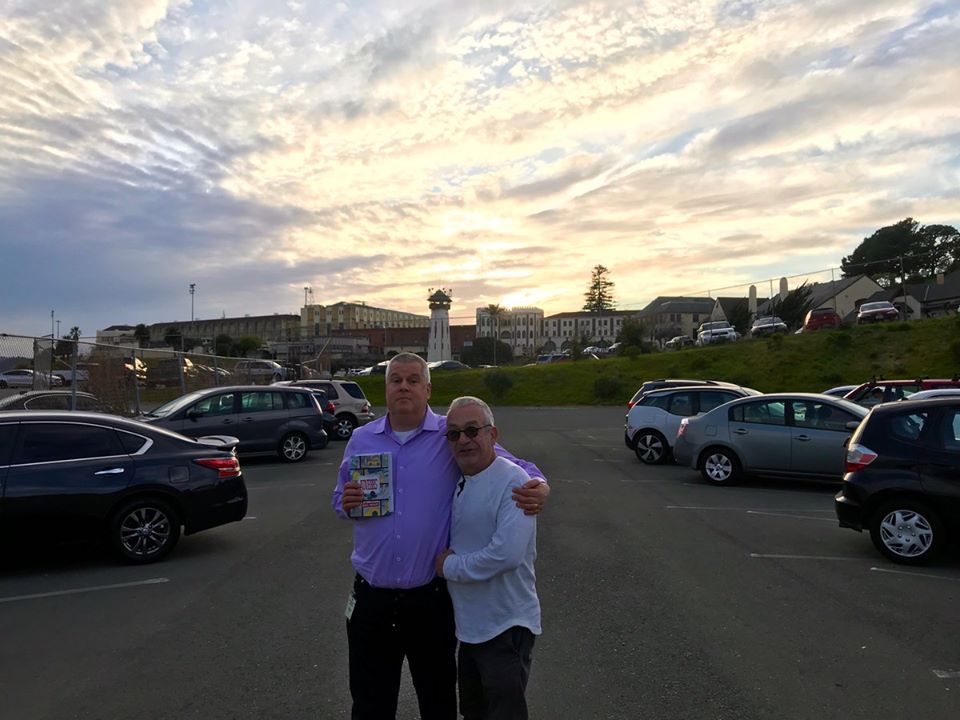

This was true for Jesse Vasquez, former editor-in-chief for the San Quentin News, who says his involvement with the newspaper and other rehabilitation programs are the reason he’s a free man today after spending half his life in prison.

“We [San Quentin News reporters] want to be an instrument of social justice,” Vasquez says. “What society expects in a prison is violence, riots, drugs, and stuff like that, but that isn’t news to the outside. Minds have been trained to think that prisons harbor the most horrible of individuals, and yet you see that they’re graduating, they’re participating in Shakespeare and putting on performances.”

Vasquez was arrested and convicted for attempted murder and assault with a deadly weapon after a drive-by shooting at the age of 17. He says from a young age, he knew he would likely fall into the prison system.

“It was the way that I lived in my neighborhood, the things that I saw led me to believe that violence was a form of conflict resolution and that was the way that you solve problems.”

His own experience growing up in the prison system made him cynical. He didn’t believe that he and others caught up in the carceral system would ever find another way forward. Then, he says, the San Quentin News gave him reason to second guess his nihilistic views. He was serving time at Folsom State Prison when he read his first copy of the paper.

“I started reading the newspaper and I kind of thought it was just state propaganda,” he says. “I had never seen a prison like this. Every prison I was at had limited programming and there was this us-against-them mentality between staff and the incarcerated.”

But then, something began to change. Vasquez decided that if he were going to be locked up, he’d rather be in an institution that at least attempted to give the inmates a creative outlet and a voice. And so, when he had the opportunity to transfer prisons in 2016, he chose San Quentin.

“I can honestly say that up until the point I got to San Quentin, I was content with being in prison,” Vasquez says. “I had come to terms at a young age that I was likely going to die in these institutions. When I got to San Quentin, that contentment shifted to where I wasn’t satisfied with dying in prison. I wasn’t satisfied with staying in prison the way prison was. I wanted to do something about it because everybody else seemed to think we could do something about it.”

Vasquez, who now manages a housing program in Oakland for formerly incarcerated people, says his relationship with volunteer staff and advisors set him up for success.

“They mentored me and helped me understand who I was and my professional capacity. That environment facilitated that growth where I’m able to navigate better. I have these skills that I developed because of the volunteers taking the time out of their day to come and visit us inside and impart to us their wisdom and understanding.”

Catalyst for Change

The San Quentin News is not only an inspiration to the incarcerated — it is a catalyst for change throughout California’s carceral system, as more prison news publications spring up around the state. Vasquez says while he was working at San Quentin’s paper, multiple prisons reached out inquiring about how to start a paper or newsletter of their own.

The Mule Creek Post at Mule Creek State Prison, The Pioneer at Kern Valley State Prison, and Solano Vision at California State Prison Solano are active prison news publications in the mold of the San Quentin News.

However, according to Steve McNamara, a volunteer advisor for the San Quentin News, while other prison publications are doing their best, they are all missing a key piece of the puzzle: civilian mentorship and support. “Some of the other prisons have begun to experiment with other papers, but of course what they really need in the beginning are volunteers who have some experience in this business and who are willing to devote time to get it off the ground,” says McNamara, former owner of Marin County’s Pacific Sun newspaper.

McNamara, an advisor for the San Quentin News since 2008, says those looking for proof that the paper has made a difference in the culture of the prison just need to look at the data behind prisoner transfers. As it turns out, Vasquez isn’t the only one who has sought to be moved to San Quentin in recent years.

“Inmates angle to get transferred to San Quentin,” McNamara says. “It used to be a scary place, and it is no more.”

McNamara concedes that the prison newspaper itself may not deserve all the credit. Rather, it is the underlying secret to the success of the San Quentin News that has turned the tide. Its proximity to the left-leaning, highly progressive Bay Area means San Quentin benefits from a wealth of willing volunteers all aiming to change the criminal justice system for the better.

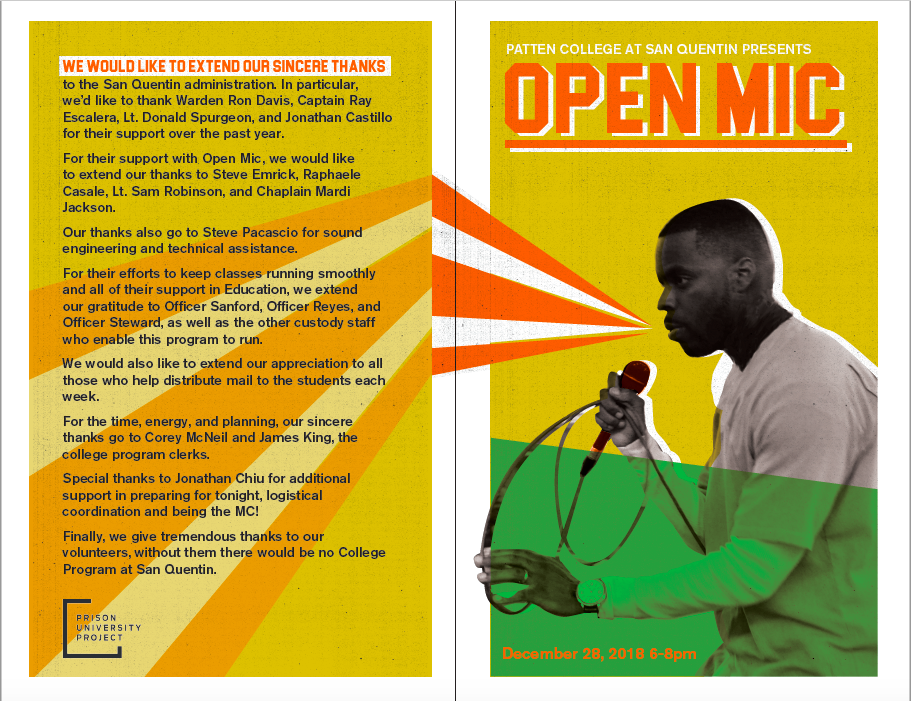

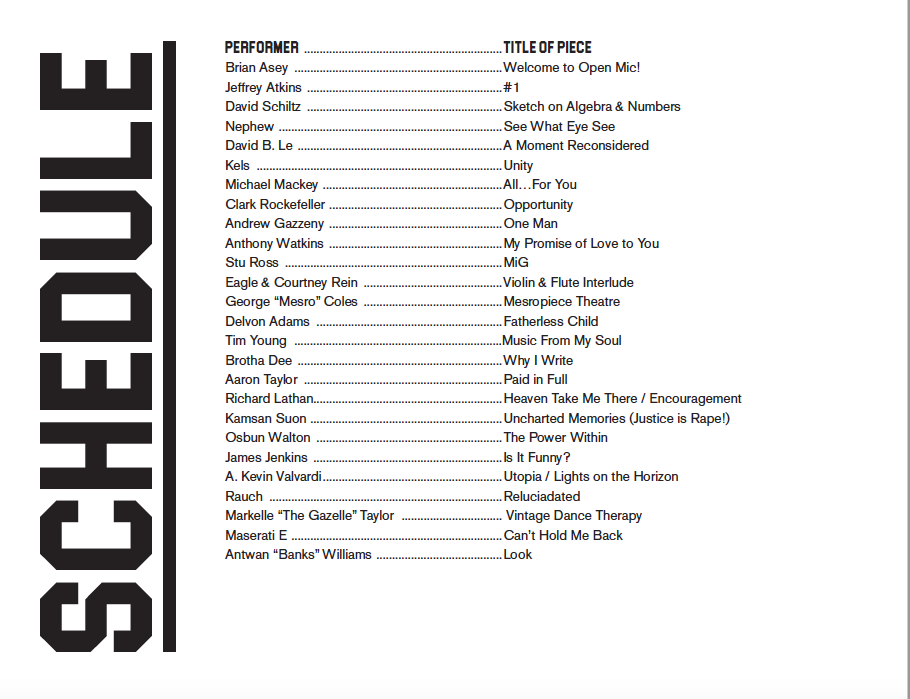

At San Quentin, the paper is just one of ample rehabilitation activities and programs aided by thousands of volunteers — all of which are intended to build skills and facilitate avenues of success for the incarcerated.

“All the programs involve a close relationship between the participants and the volunteers who come in,” McNamara says. “They are people who are there predisposed towards believing in the reform of the criminal justice system.”

Crime & Punishment

Although the Bay Area’s left-leaning population may drive support for programs like the San Quentin News, jailhouse journalism isn’t favored among all Bay Area residents.

“These guys are individuals who’ve committed grave and violent acts against innocent victims,” says Marc Klaas, founder of the KlaasKids Foundation, a victim’s rights organization based in the Bay Area. “They’ve been put in San Quentin and they’re put in these prisons because they’ve lost their right to public access. They’ve lost their right to be able to express their views.”

Klaas is a public figure who speaks on behalf of many victims of crime and their families. His daughter, Polly Klaas, was kidnapped from her Petaluma home at knife-point during a slumber party and later strangled to death at the age of 12 in 1993. Polly’s killer, Richard Allen Davis, sits on San Quentin’s death row.

Since the age of 12, Davis had been in and out of the prison system for both misdemeanors and felonies. In June of 1993, he was released on parole from the California Men’s Colony in San Luis Obispo after serving only half of a sentence for another violent kidnapping in 1984.

“When my little girl was kidnapped and murdered in 1993, we had a crime epidemic in the entire United States, and it was because there were some very soft-on-crime policies,” Klaas says.

“The guy that kidnapped Polly, for instance, had been convicted twice previously of kidnapping. For his second kidnapping, he was released from prison after serving only eight years of a 16-year sentence, and only three months later my daughter was dead at his hands,” Klaas said. “Now 27 years later there’s a movement to ensure that he’s treated fairly?”

Davis’ extensive criminal record fueled advocacy for the passage of California’s controversial “three-strikes law” for repeat offenders in 1994. The law significantly increases prison sentences for convicts with two or more previous felonies, which has led some to be handed life sentences for non-violent crimes.

Prison reform advocates say “three strikes” leads to overcrowding in prisons, perpetuating mass incarceration, and deters incarcerated individuals sentenced to life without parole from participating in effective rehabilitative programs.

Klaas doesn’t entirely disregard support for rehabilitation but says it shouldn’t apply to everyone.

“I believe there are individuals that can be rehabilitated. For instance, I think that people who find themselves in prison because of drug-related situations can be treated and moved back onto a positive path, but once you get into the business of hurting people, of violence against people, I think you’ve taken a step too far and I don’t know if these are people we should be rehabilitating.”

Restorative Justice

The message of victim’s rights advocates has long resonated with political leaders and, according to UC Hastings’ Hadar Aviram, that tough-on-crime position is at once understandable and a roadblock to meaningful prison reform.

“I think that it is very important to listen to victims. And at the same time, it is also important to remember that victims should not be the moral arbiters for every public policy that has to do with justice,” Aviram says. “One of the things that we’ve seen in the culture of California is that victim advocacy groups and victim’s rights movements hijack the conversation to the point that no politician on the right or the left can afford to be seen as soft on crime.”

UC Berkeley law professor Jonathan Simon believes that rehabilitative measures should be offered to all prisoners. According to Simon, a legal scholar and historian, they are an effective means of addressing the underlying reasons individuals commit crimes, particularly violent offenses.

“Undoubtedly, the most serious crimes generate strong emotions, but we’ve enhanced it by myopic focus on the act and unwillingness to consider the person’s life courses,” Simon says.

“If we’re going to incarcerate people we should give them access to education and other things that allow them to protect their integrity.”

To Simon, San Quentin’s COVID-19 crisis is proof that California’s prisons have reached a breaking point and that the correctional system is in need of a serious overhaul.

“When institutions become so toxified that they’re not able to correct themselves by responding to the needs of the humans that they’re managing, it’s time to look for radically different solutions,” he says. “I think it’s hard to conclude from this COVID crisis that we’re not there.”

And yet, as damaging as the pandemic was to public perceptions of CDCR, and as much as the outbreaks amplified public sympathy for the incarcerated and sparked discussions around reform, Simon isn’t holding his breath. With litigation to thinning inmate populations at a standstill, he recognizes a powerful set of beliefs aligned against change.

“I think it’s a sign of how durable some of these crime myths are, that even at a time when there’s a lot of agreement that we need to change things, it’s been hard to convince the state to dramatically shift,” Simon says. “There’s a whole series of beliefs that are well worn into our legal thinking about imprisonment. One is what I like to describe as the myth of debt, that somehow there’s a debt that a crime creates, and unless somebody pays the full amount of it back, that everybody else has been cheated in some way. It’s powerful. It leads to the opposite, that is a system that can’t stop collecting.”

Still, Simon and other prison reform advocates do see signs of movement — chiefly in the engagement of the young activists who speak out when they recognize injustice.

“The Black Lives Matter movement, as well as lot of other Americans who joined protest movements over the summer in response to George Floyd’s murder, are pretty significant,” he says, “because it’s the first time we’ve ever had a social justice and racial justice movement that’s squarely focused on the criminal-legal system as the [primary] target. I think that’s very positive in terms of driving change.”

While activists around America have marched in the streets for those historically silenced, the incarcerated journalists inside San Quentin continue to fight — and write — for justice. In that battle, a pen and paper are their weapons of choice.

“I have a saying for people who want to voice themselves,” says San Quentin News editor Juan Haines. “I tell them, ‘Pick up a pen, hold in firmly in your hand, and push it forward.’”

Lily Sinkovitz is a contributing writer. news@sfweekly.com

“I’m just a regular guy, a voice in the middle of a sea of voices that don’t seem to matter to most—which is why we may forever be misrepresented unless we speak for ourselves.” —D. Watkins

“I’m just a regular guy, a voice in the middle of a sea of voices that don’t seem to matter to most—which is why we may forever be misrepresented unless we speak for ourselves.” —D. Watkins

Michael David Lukas

Michael David Lukas