Last fall, Voice of Witness, an organization that advances human rights by amplifying the voices of people impacted by injustice, held three classes that introduced Prison University Project students to the oral history process. Read more about the series of workshops by clicking below, and check out students Steve Brooks and Joe Garcia’s stories published on the Voice of Witness Blog.

The Voice of Witness education team is always looking for opportunities to create deeper engagement and partnership with the communities represented in our book series, so we can ensure our educational resources are reaching the students who need them the most. That’s why with the launch of our newest book, Six By Ten: Stories from Solitary, we’ve been working with the Prison University Project (PUP) at San Quentin State Prison to share VOW’s ethics-driven oral history process with their students.

The PUP college program offers San Quentin inmates free courses in the humanities, social sciences, math, and science, as well as intensive college preparatory courses in math and English. Working with PUP Academic Program Director, Amy Jamgochian, I developed three classes that would introduce students to the oral history process and give them an opportunity to practice their interview skills, both as an interviewer and narrator, as well as their editing skills.

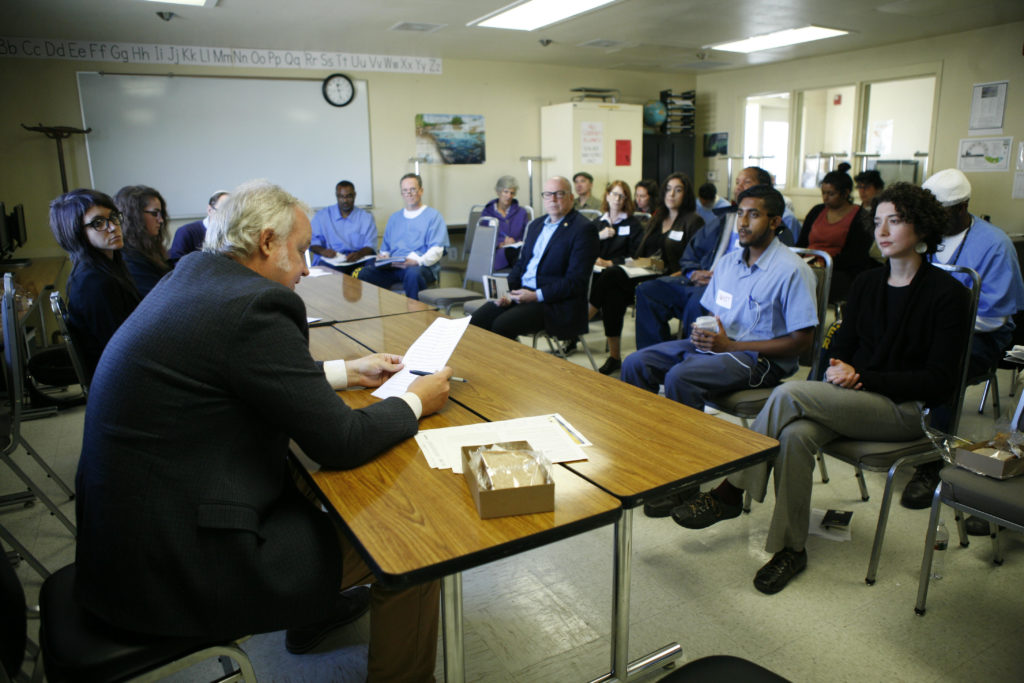

Following weeks of planning, logistics and pursuing security clearances, I kicked off the first class by pairing students up to a share a story with each other related to their first names. It was a great way to warm everyone up to storytelling – after sharing their stories with the group, many of them realized their stories had something in common!

We then read Hani Khan’s story from Patriot Acts, which helped students begin to think about the relationship between interviewer and narrator in the oral history process – in particular the types of questions (and listening) that inspire thoughtful, detailed stories.

I was inspired by how adept the students were at contextualizing oral history, posing powerful questions about the nature of history—namely who makes it and who writes it. They quickly made connections between oral history and traditions like West African Griots, and modern day emcees.

In order to prepare ourselves for interviews during our second class, our first meeting finished with an exploration of the question, “If you had a meaningful story to share with someone, what would you need to feel safe, to feel brave?” There were many lively responses, and the class felt very connected to issues related to respect, representation, and the importance of agency over one’s own story.

When I arrived for our second class, I discovered that we were going to be in a different classroom, and one right next store to a room where there was an open-mic performance going on. Not exactly ideal when you’ll be conducting oral history interviews! However, this seemed to bother me more than it did the students, and they came in ready to conduct their interviews. After a while, we were able to turn the performance next door into part of our interview experience, as we acknowledged the applause next door as an appreciation of our interview skills!

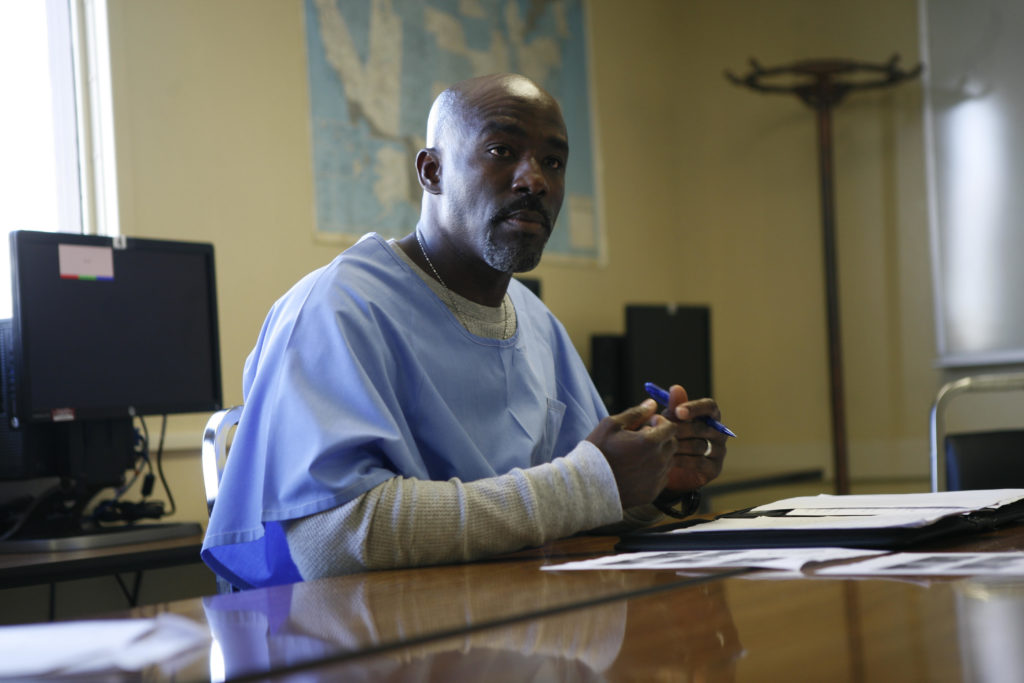

The interviews were not without their challenges, however. Due to prison requirements the students were not able to use recording devices for their interviews, and instead took copious notes while interviewing their partners. It was certainly an exercise in maintaining focus—both when listening to your narrator’s story, and in the ability to capture the meaningful moments of the story on paper in real time.

After the interviews were completed, partners shared their notes with each other and had a bit of time to incorporate this material into their existing story drafts. Watching this process unfold, it became clear to me that this approach to oral history – and the challenges incarcerated people face documenting their stories – should be incorporated into our curriculum for Six By Ten. Before the end of class, I reminded students that our third and final meeting was going to be devoted to editing their personal narratives.

Looking ahead, we will be using the VOW blog to provide an online platform for these students to publish their stories. In our last class, our first task was to make sure everyone was clear about the process of getting their oral histories onto the VOW website. After some editing work, the stories would be typed up, proofed by the students, and then sent to the Public Information Officer for publishing clearance.

As we began our editing session, it was interesting for students to compare the editing work they had done in their formal writing, and the choices made while editing their personal narratives. Many concepts and techniques carried over, such as clarity and quality of detail, but students were also able to use different editing techniques to highlight moments in their stories that included sensory detail, a clear storytelling arc, and an overall intuitive sense of what makes for a compelling story. At the end of our editing session, I asked if a few students would be willing to read their narratives to the class. Everyone volunteered and we finished our work together in a very supportive story sharing environment.

Before parting, I took a moment to reflect on how much we were able to touch on in just three classes: oral history techniques, editing, the concept of “people’s history,” several excerpts from the VOW book series (including Six By Ten), the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, quotes from Chimamanda Adichie and James Baldwin, and guiding principles for ethical storytelling. I was also glad to be able to leave some VOW books for the PUP library, so other students in the program will have access to the stories and can make connections with the lives and experiences of our narrators.

I certainly hope this is only the beginning of our work with the students of the Prison University Project. We can’t wait to share these students’ stories with you in the coming months!

Please note that the Prison University Project became Mount Tamalpais College in September 2020.

As a future entrepreneur, taking Business 101 was a blessing. I have learned to build houses from the ground up and I plan to begin my own house flipping business upon release. This course provided me with valuable information that would increase my chances to succeed in my business, specifically the financing and marketing aspects.

As a future entrepreneur, taking Business 101 was a blessing. I have learned to build houses from the ground up and I plan to begin my own house flipping business upon release. This course provided me with valuable information that would increase my chances to succeed in my business, specifically the financing and marketing aspects. This summer, I had the great pleasure of teaching Business 101: Introduction to Business, with Will Bondurant and Jennifer Lyons. We each have expertise in distinct areas of business—Will is in marketing, Jen is finance and economics, and I’m operations. After we’d covered the subject-specific material, we spent the second half of the semester talking more broadly about entrepreneurship, communications, professionalism, and ethics, while students worked on their business plans.

This summer, I had the great pleasure of teaching Business 101: Introduction to Business, with Will Bondurant and Jennifer Lyons. We each have expertise in distinct areas of business—Will is in marketing, Jen is finance and economics, and I’m operations. After we’d covered the subject-specific material, we spent the second half of the semester talking more broadly about entrepreneurship, communications, professionalism, and ethics, while students worked on their business plans.