We are thrilled to announce that we have reached a historic agreement with the administration at San Quentin State Prison around the use of technology by Mount Tamalpais College students. As we resume in-person classes, we will have laptops, charging carts, and printers available in the prison for student and faculty use. Students will be able to use laptops during class or in the education building.

Laptops will allow students to conduct research independently and access learning supports and word processing capabilities. They may also access online resources available on the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation Canvas Learning Management System. This initiative will begin on a limited basis, and will gradually be expanded over time.

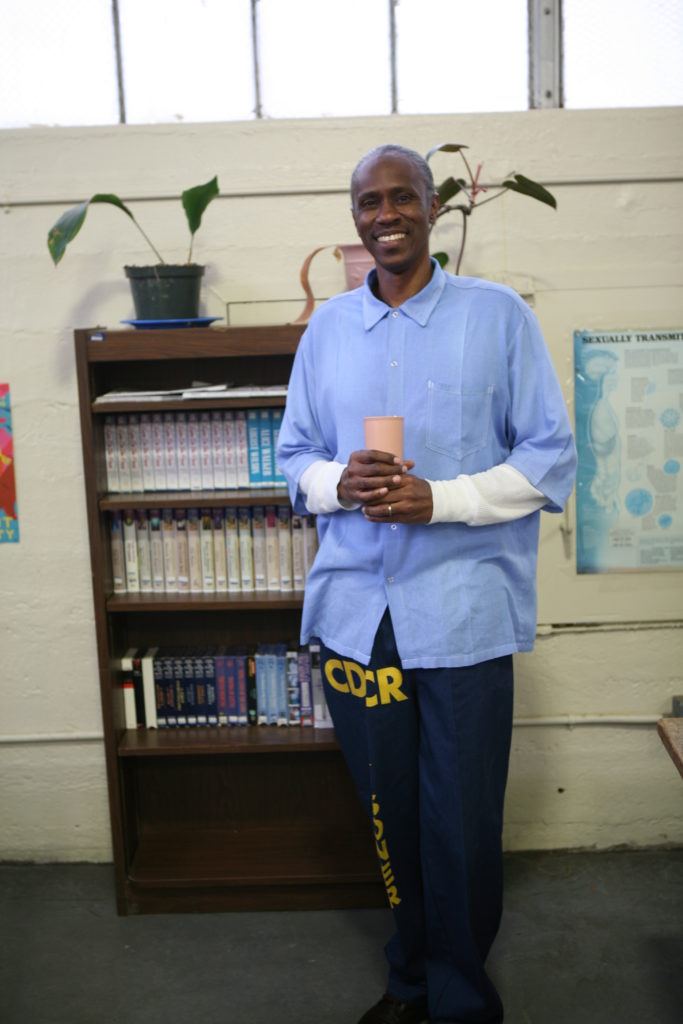

This agreement represents a significant gain for our students. For the past twenty-five years, students have not had access to technology or computers during their studies. They have handwritten work and conducted research using printouts and course readers sourced by faculty members and a limited collection of books. In fact, very few programs at San Quentin have been allowed to bring any technology or equipment inside the prison, resulting in a marked technology gap among incarcerated people upon their release.

Ultimately, we hope that students will have access to the laptops during lockdowns or quarantines and be able to engage in synchronous and asynchronous remote instruction as needed. We are now in the process of purchasing and processing the equipment for use as in-person programming resumes.