Prison University Project student Rahsaan “New York” Thomas writes in The Marshall Project about his experience working on the award-winning Ear Hustle Podcast from inside San Quentin.

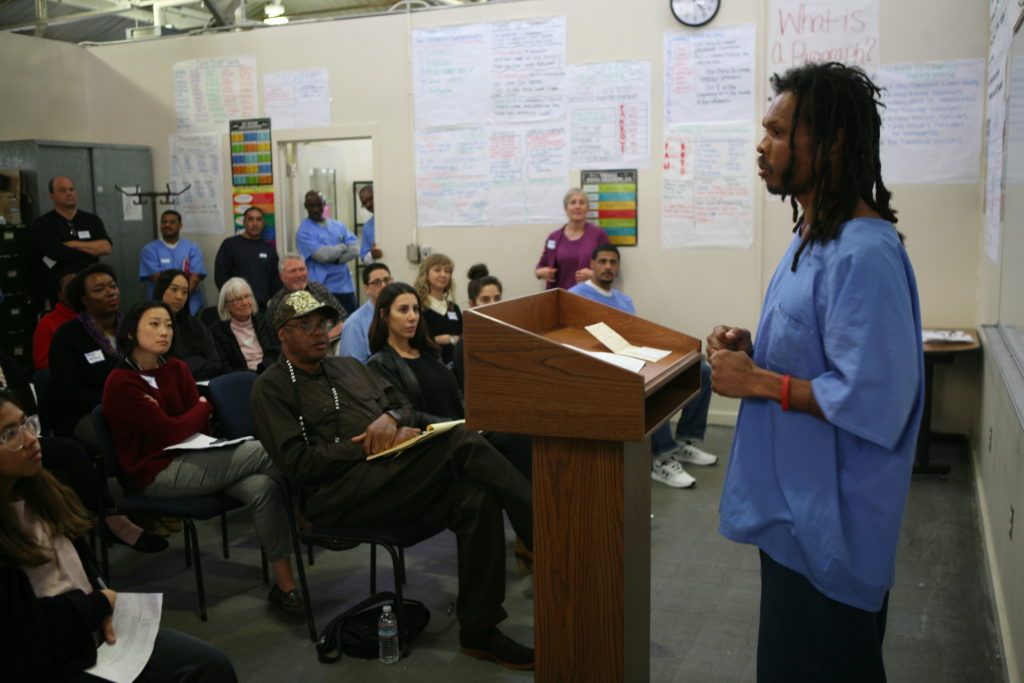

The sun shines brightly through the gated windows so I grab a pair of Sony headphones and the Tascam (a portable audio recorder) and leave the office with my co-worker, John “Yahya” Johnson, an intellectual Muslim brother out of Oakland. Curious as to how many people behind bars have seen the romance movie “The Notebook,” we venture outside to the yard to find out. I walk up to the first guy I see, someone waiting on the sidelines to play basketball.

“Hey man, can I interview you about the classic romance movie called ‘The Notebook?’”

“I’ve never seen ‘The Notebook.’”

“So what’s the best romance movie you have seen?”

“’Baby Boy.’”

I laugh because Baby Boy, an urban tale about a childish young man who needs to grow up in order to raise his son alongside the mother, is not what I would consider a classic romance movie.

Then I remove a release form (to have the man I’d just interviewed sign) from a green binder with an Ear Hustle logo stuck on the cover.

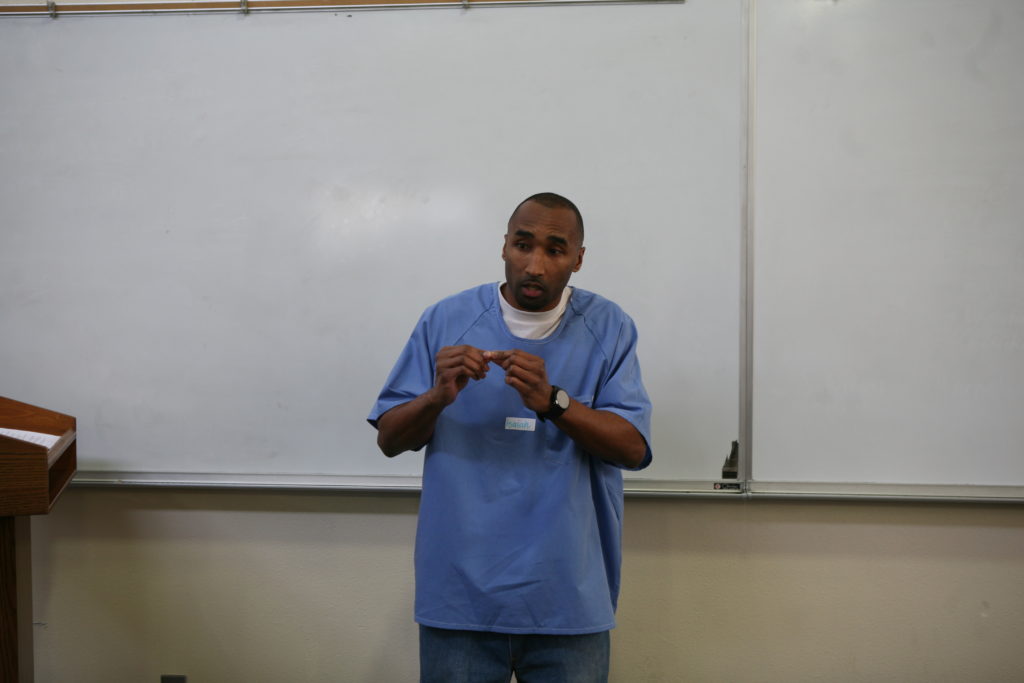

Ear Hustle is the award-winning podcast about life inside prison—specifically my prison, San Quentin—that has around 30 million downloads in total. It’s the brainchild of Nigel Poor, a professor who taught for years at San Quentin, Earlonne Woods, a man who was serving a life sentence for attempted robbery under California’s three-strikes law, and Antwan “Banks” Williams. The original plan was to circulate the show only inside the prison, but then they got permission to enter a Radiotopia “Podquest” contest.

No one at San Quentin knew how to do a podcast, but they entered anyway—and won. In 2017, Ear Hustle launched to critical acclaim with “Cellies,” featured on the Today Show, tallying nearly 2 million downloads.

As a reporter for the San Quentin News, I covered the rapid rise of the podcast as it defied the gravity of being produced inside a prison. From right next door, I cheered at the accomplishment of something that no incarcerated people had ever been able to do so effectively: reach millions of people.

But in 2018, Gov. Jerry Brown commuted Earlonne’s sentence, and he became a free man; his job as co-producer and co-host was suddenly available. Eager to learn how to tell more effective stories, I jumped at the chance to apply. That meant getting grilled by Nigel, while Earlonne warned me that I probably should just settle for being a producer. It would be hard to follow a guy with a perfect radio voice, I knew.

But Earlonne surprised me a few weeks later, saying, “It’s you, dog. You gonna be the new co-host.” I felt proud to be chosen, of course, but even more scared about following his act. Earlonne’s charisma and rapport with Nigel are a huge part of the podcast’s success. Plus he’s a three-striker, which gets him a measure of sympathy, whereas I’m convicted of murder. Would the world accept me becoming the voice of Ear Hustle?

A few nervous month later, it was decided that Earlonne would actually continue with the show by producing and co-hosting certain stories that covered the other side of incarceration: what it’s like to be on parole. I felt relieved from the pressure to single-handedly maintain the show’s success.

On the yard, Yahya and I continued to ask people about “The Notebook” for an episode about “dating while on parole” called, “I Want the Fairy Tale.” We interviewed about eight more guys at random. A few declined to speak on the record, but most hold Ear Hustle in high regard and were eager for a chance to shine. After finding out that the majority of men at San Quentin won’t admit to being chick-flick fans, we headed back to the media center. There, Nigel sat at an iMac computer editing audio using ProTools software. Across the small space, Antwan worked with Pat Mesiti-Miller, an audio engineer, on sound-designing.

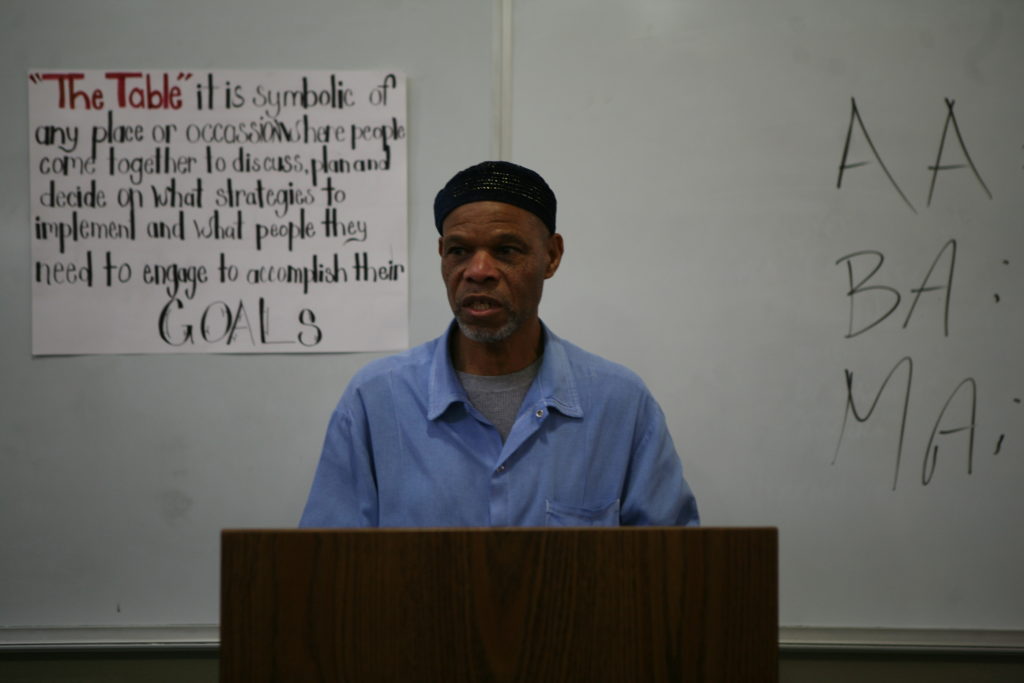

Nigel and Pat are our supervisors, but it feels like the only difference between us is that they get to leave the prison and go home at the end of the workday. Otherwise we are colleagues. I weigh in on stories and how far we can go without losing the respect of the incarcerated people who trust us. (We often have to advise the men not to give us too much information about themselves, for their own privacy and security in here, no matter how many downloads they think their most dramatic story will get.)

I’ve heard it said that there can be no communication until we sit together as equals. Working for Ear Hustle feels like that. In most prisons I’ve been to, it didn’t feel like I could work with society to accomplish anything. Like so many in lockup, I felt alienated from you. But now I feel like a productive member of both the inside and outside community.

Besides working with my colleagues, I also interact with Lieutenant Robinson, the public information officer here. He’s the type of prison official who supports positive endeavors and empowers us to carry them out. It’s his signature on a memo of permission that allows me to walk the yard conducting interviews. For the first time in my life, I enjoy talking with a correctional officer—it’s actually fun to hear him clown around when he records the approvals that we play during each episode.

Today the Lt. came to weigh in on our “Inside Music” episode. A microphone attached to what looks like a robotic arm extends to each side of a small table. ProTools is set to record.

“I went back and forth” on approving this one, the Lt. said into the mic, “because I know there’s a genre you guys missed. There is no country music in this episode. [But], begrudgingly, I am Lt. Sam Robinson at San Quentin State Prison, the public information officer who approves this episode.”

Producing a podcast from prison isn’t all green lights, though. The “Inside Music” episode went up behind schedule because it had to be further cleared by the administration before it could be released, and that happened a day late. They check for “security and safety” concerns.

It can be frustrating, but then I remember: There’s probably no other prison in the world where a man convicted of murder would be allowed to use his time so productively doing something he loves—bringing joy, understanding, and entertainment to the public about the human nature of people behind bars. Because of how much harm I caused many families, it doesn’t feel like I deserve to be co-host of anything. At the same time, I’m hungry to make meaning out of destruction.

With each episode, I wonder if some listener will object to me co-hosting.

At the end of the day, I return to a cell that I share with another incarcerated person. I grab my shower stuff and troop back down five flights of stairs to the shower that’s down there. It’s full. A line of 12 men stand under a small pipe with nozzles streaming water, each just two feet apart.

I wait on the side until a shower becomes available and wash myself there, in front of everyone. About 20 minutes later, I’m back in my cell as a correctional officer locks the door for the night. I’m in prison.

But before walking away, he hesitates, shuffles through some envelopes and says, “Thomas.”

“95,” I answer, indicating the last two numbers of my prison identification number.

“You got some letters.”

He hands three through the side of the gate. I quickly scan the return addresses. One is from someone I don’t recognize.

I open it and commence reading. It starts with, “I heard you on Ear Hustle.”

I grin.

Please note that the Prison University Project became Mount Tamalpais College in September 2020.